Appurtenant rights covered a wider range of produce than appendant rights and these will be discussed in later posts; our main concern in this post being common of pasture appurtenant. The right to graze animals on the waste and commonable grasslands of the manor. This was probably the oldest of the appurtenant rights although, as far as we can tell, the legal distinction between COPA and COPR was not made until the 16th century. Given that the necessity to overwinter their oxen and horses on the waste was as great for the unfree tenants as the free tenants we might wonder what rights if any the unfree tenants held before this time.

The historical view of the origin of rights of common presumed that a population of ancient Germanic freemen had owned and worked the land in common. Rights, as such, did not exist, there was no need for them. When their descendants, in the form of the Anglo-Saxon’s, came to Briton the natural competitive instincts of men created a society where some individuals prevailed over their fellows reducing them to little more than serfs or slaves. This was the view of Sir William Blackstone who referring to the pre-conquest villagers referred to them as “a sort of people in a condition of downright servitude, used and employed in the most servile works, and belonging, both they, their children, and effects, to the lord of the soil, like the rest of the cattle or stock upon it. These seem to have been those who held what was called the folk-land, from which they were removable at the lord’s pleasure”.

In such a society the issue of rights of common was moot. Enslaved people had always had to grow the food which sustained them and from the perspective of their overlords allocating land to them for this purpose was just as much for ‘the necessity of the thing’ as allowing access to the waste to graze their oxen on. Except that ‘their oxen’ were probably not ‘their’ oxen at all.

The social conditions of the time were described by Elizabeth Lamond[1] in the 19th century, “The villein was not paid wages like the modern labourer, but in an ordinary way he worked three days a week on the domain land, he gave besides extra days in autumn, and performed other incidental duties, and he had in return his meals on some of the working days, and a holding (virgata) of about thirty acres, which his lord stocked with a yoke of oxen and half-a-dozen sheep when the villein first entered on his tenancy.”

If we take a typical Domesday entry, for example that at Rampisham[2], we find there is “Land for 6 ploughs, of which 3 hides are in lordship; 2 ploughs there, with 1 slave; 10 villagers and 6 smallholders with 3 ploughs”. In such a society it is highly unlikely that the eighteen oxen required to work the villager’s ploughs were ‘owned’ by the villeins themselves. If in the 13th century, as Lamond suggests, the lord provided the oxen for the tenant to use, but not own, it is highly likely that a similar arrangement was in place under the Anglo-Saxons. If this was the case the Anglo-Saxon thegn and Norman lord, having appropriated the waste to themselves, were doing no more than graze the oxen on their own land for which no right of common was needed.

Life for the Anglo-Saxon villagers improved after the Conquest; “On the arrival of the Normans here …[they] give some sparks of enfranchisement to such wretched persons as fell to their share, by admitting them, as well as others, to the oath of fealty; which conferred a right of protection, and raised the tenant to a kind of estate superior to downright slavery, but inferior to every other condition”.

At the beginning of the 14th century “by a long series of immemorial encroachments on the lord”, the villein had so far progressed themselves to become true tenants of the manor. In exchange for “a mixture of [3]cash, payment in kind, labour services and feudal incidents”[4] they became a class of tenants that Sir Edward Coke called ‘tenants in villeinage’. Between the 14th and 16th centuries, villein tenure was to transform into copyhold tenure[5] although precisely how and when this process took place is ill understood. The differences were important both legally and practically as we might presume that during this period the economic status of the villein had perhaps improved to the extent that [s]he now owned their own animals. For them to continue to use the waste the unfree tenants had to acquire rights of common and, since COPA could by this time no longer be created, they had to be COPR.

It is unlikely that there was any significant or practical difference between the two forms of right. The freeman was of higher status than the villein and a grant of land to him was a more formal process but that does not mean to say that he was treated more generously than his unfree neighbour, the exigencies of agriculture take no regard of a man or woman’s position in the hierarchy. The suspicion must be that the rights for both the free and the unfree must have been very similar even though legal disputes over these rights may have been handled in different venues. It is not even clear that in these earlier centuries there was much distinction made between the types of tenure. Halbsbury in a footnote to a case before the courts in 1874, noted that the presiding judge had concluded, “that distinction [between free and unfree tenants] not being recognised by those who practically managed these things in days of old, the tenants of these demesne lands under the lord [the villeins] did enjoy the same rights of common over the wastes as those persons to whom lands had been conveyed [the free tenants].”

The differences between the two types have already been outlined but we may say a little more about them. Firstly the range of men or women who could be granted a right was enlarged. COPA was only granted to free tenants of the manor but COPR could be granted to both freemen of the manor, freemen not of the manor [after Quia Emptores], copyholders, leaseholders and even towns who, through their corporation status, could hold rights. Indeed COPR could often be attached to a public office so that for example in any parishes the Overseer of the Poor was allowed to keep a few animals on the waste to earn income and support the poor. It was even possible for the tenants of one manor to hold COPR in the waste of another. At the end of the day the grantor of the right was pretty much free to do what he wanted.

Whilst the initial grant of COPR was to an individual person it was always attached, or appurtenant, to a particular tenement, and the right passed to the new owner when the tenement was conveyed to them. As Sir Edward Coke pointed out however the right itself was rarely mentioned explicitly in the conveyance it seeming to be legally sufficient to include in the deed a phrase such as “with all commons and commonable rights’ therewith used or enjoyed”.

COPR was more vulnerable to loss than COPA and two problems frequently arose. If the owner of the right had not exercised it for more than a year it would be lost and secondly, if the owner of the waste sold a part of it then COPR was extinguished. This if of course in contradistinction to COPA where if part of the waste was sold a part of the right went with it. Finally of course, as with COPA, all rights of common were extinguished by parliamentary inclosure.

Remembering the term ‘levant and couchant’, which referred both to the types of animal that could be grazed on the waste, as well as the number of animals COPR was not limited to animals levant et couchant [Cattle, horses and sheep]. COPR allowed donkeys, pigs, geese and goats and, as Halsbury puts it, “all other animals which can be sustained upon the common” to use it. Such rights however were not universal, manor [A] might have allowed pigs but no geese, whereas a neighbouring manor, [B], might have allowed geese but no pigs.

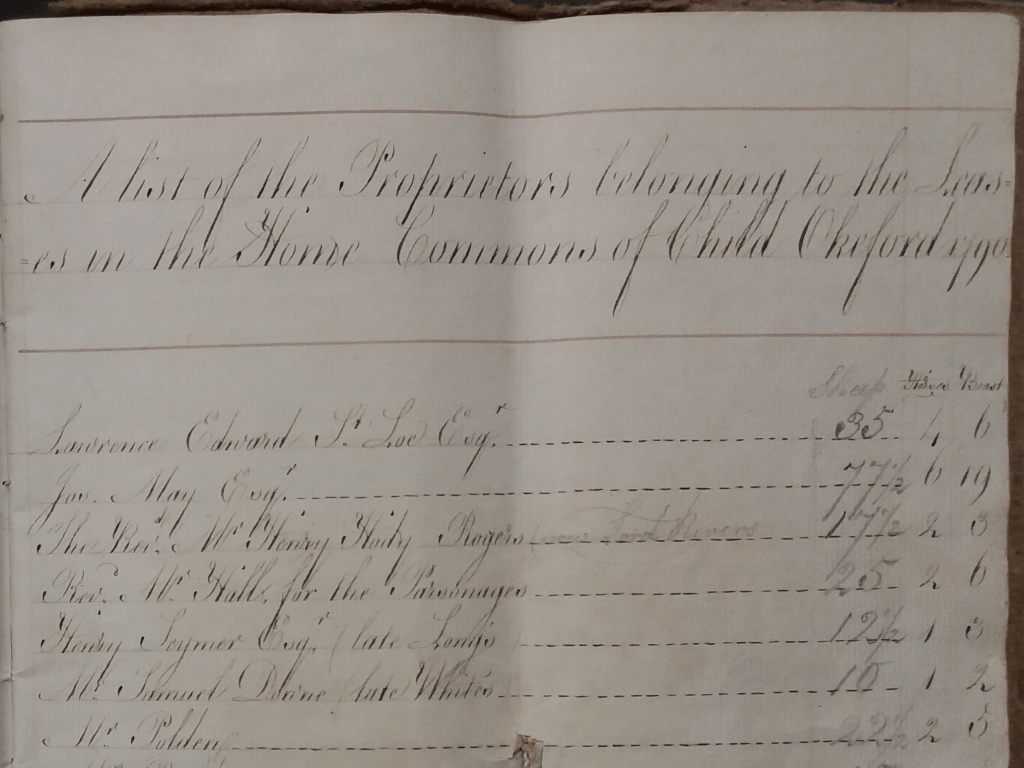

In respect of the other meaning of levant et couchant, the number of animals that could be put on the waste it was usually limited to, in the legal jargon, ‘a number certain’. This was usually related to the acreage of the land to which the right was appurtenant or to its rental value. Sometimes it is not clear how the numbers were arrived at. This picture below is a crop from survey done at Child Okeford of rights of common over the waste. It is dated 1790 but it is an egregious document which cannot be dated accurately.

Many of the landowners listed are still there [or their families are] in the 1840 tithe survey and there is no clear link between the areas of land they held then and the numbers they could keep on the common.

Some manors allowed grazing ‘sans nombre’, but in practice this did not amount to a free for all. In law it simply meant that the number was limited to the number of animals levant et couchant that could be supported on the waste. Indeed it appears that if a commoner did claim he could depasture an unlimited number of animals on the waste the courts usually dismissed the case. Despite this there is little doubt that many commons were over stocked and that little was done about it by the manorial lords.

How rights were organised at Rampisham, and doubtless elsewhere, is the subject of the next post.

[1] Elizabeth Lamond: Translation and commentaries on ‘Walter of Henley’s Husbandry’ 1890.

[2] RAMPISHAM: There is no entry for Evershot in the Domesday Book. Or at least none that I can find.

[3] FEUDAL INCIDENTS: ‘The transformation of customary tenures in Southern England’ Mark Bailey, BAHR 2014

[4] FEUDAL INCIDENTS: ‘The transformation of customary tenures in Southern England’ Mark Bailey, BAHR 2014

[5] VILLEIN TENURE & COPYHOLD TENURE: Copyhold tenure differed from Villein tenure in three principle ways. First their was greater legal protection under the common law. Second the servile incidents, working on the land etc disappeared and the copyhold was now held by an entry fine [fee] on assumption of the tenancy, an annual rent and a heriot payable from the estate on the death of the tenant. Lastly whereas under villein tenure the tenant could [in theory at least] be ejected ‘upon a seigneurial whim’ the tenancy was now more of a contract which could be protected at law. Villein tenure was recorded in the court roll of the manor and matters concerning it were decided only in the manor court. Matters concerning copyhold were decided in the king’s courts.

Categories: In Depth