In medieval times a court simply meant a formal assembly, and at the level of the manor there were two types. The first, the Court Baron, was concerned with the regulation of the manor itself and indeed for the life of the manor itself it was the most important of the two courts. In one of those archaic terms of the time, the Court Baron was said to be ‘incident’ to the manor. In other words every manor had to have one and if it did not it was not a properly constituted manor. The tenants of the manor had to attend the court and there had to be at least two to form what was known as the ‘Homage’. Fewer than two tenants and the manor ceased to exist.

The Court Baron was primarily concerned with tenancy issues together with minor misdemeanours and breaches of the customs of the parish whilst the second type of court, the Court Leet concerned itself with wider issues concerning the King’s or Queen’s Justice. All manors had to have a Court Baron but only occasional manors had a Court Leet. In this section I will be looking at the workings of the Court Baron and Leet of the Manor of Rampisham towards the end of the life of the manor. A fuller more general picture of the manorial court system can be found here In Depth The manorial courts.

The working of the Court Baron is shown in three examples of problems arising at Rampisham and Evershot. The first comes from a survey of the Manor of Rampisham taken in 1806.

|

Reserved Rent |

Heriot |

Land Tax |

Held during the lives of |

Ages in 1806 |

Observations |

|

|

|||||

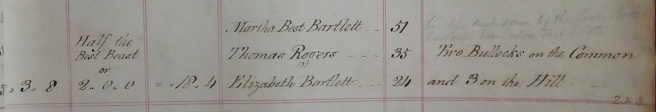

The extract concerns the copy hold tenure of Martha Best Bartlett. Her annual rent was 3s 8d and she held the land for three lives, her own, Thomas Rogers and Elizabeth Bartlett, presumably her daughter. Another part of the page gives details of the land she actually held and is not shown but for Martha the most sinister part of the survey is the part written in pencil above the note ‘Two Bullocks on the Common’, “Her life dont [sic] seem by the Lords book to have ever been upon that estate”.

Next on the 30th July 1825 the Overseer of the Poor at Evershot recorded in his accounts “Farmer Fountain giving notice that all persons will desist from carrying fire in the Street; that is to say from one house to another it being considered dangerous during this extremely dry weather 1s”.

Finally on the 2nd August 1854 Martin wrote rather indignantly,

|

2nd August 1854 |

Attending workpeople in Nine Acres Tom Hows Stallion broke into my Field with my Mare |

Thomas How was a ‘Carrier and Corn Factor’ and no doubt found it convenient to breed his own horses but one senses Martin was not impressed.

In any group of people living in close proximity and dependent in large part on each other needed some form of regulation. The responsibility for this in the early centuries was down to the Court Baron of the manor. This was not a democratic organisation as it was composed only of the lord of the manor and the free tenants [In Depth: A simple guide to land tenures].

In time the function of manors tended to decay and sometime manors could disappear. Hutchins is full of entries recording that such and such a place was formerly a manor. The need for some kind of local administration remained however and devolved to the parish in which the manor was sited. The villagers who took on the administrative role being known as the Vestry.

There was still a need however to regulate the agricultural functions of the manor and where an active Manor existed the Court Baron still had an important role in passing and enforcing what were effectively manorial by-laws. In the examples given above, the record of copyhold tenancies, the prevention of fire within the village and the maintenance of good fences, were all problems that were dealt with by the Court Baron. It was precisely this sort of thing that the court dealt with.

On a day to day basis the running of the manor was devolved to a range of ‘officials’. At the top was the steward charged with its overall supervision and probably having some professional experience as Martin indeed had. In large parishes Stewards such as Martin could not be present the whole time however and under him there was often a reeve who undertook the day to day running of the manor. He in turn might have a small number of “field tellers, eveners, field reeves [and] haywards”[1] to manage the fields. It was in their hands as to when ploughing, sewing, and harvesting took place but they also organised the clearance of drainage ditches, weeding the crops, maintenance of the hedges and ejecting any stray animals that broke through from the grazing lands. Most of these people were villagers whose remuneration, if any, was minimal.

Once a year [or as often as the lord required] a meeting of the whole parish was called, a sort of annual general meeting. Technically the meeting was the convening of the manorial court. There were two formal courts held at Rampisham for as well as the Court [2] Baron it also operated a Court Leet.

The Court Leet was not incident to the manor, indeed it was originally no part of the manor at all. In ancient times the Sheriff of the county held a court or tourn twice a year “for the Punishment of Breaches of the Peace, Misdemeanours, Encroachments, Nuisances and other Offences arising with in it’s particular precinct”[3] In large counties it was more convenient to hold the court nearer the manors and townships and some manor’s were appointed to host the court. The court leet really only dealt with minor problems although “it may also inquire of all other Offences under High Treason, as are of a publick nature, and committed within its Precincts”.

The Court Leet was also known as the View of Frankpledge and whereas the court baron originally only applied to the free tenants of the manor, the court leet applied to all inhabitants of the manor, both free holders and copyhold tenants. They have not quite died out as at least one court leet survives in Dorset to this day at Wareham.[4]

At Rampisham, and doubtless elsewhere, there appears to have been a combining of these two courts [see below]. The functions of each court are intermingled in the record. We are lucky in that in the Dorset History Centre the Court Roll [now a book rather than a roll] survives for the period 1815 -1852 when, due to lack of any more pages, the records end. Rampisham Court was usually held in November by the Steward acting for the lord of the Manor and John Martin is first mentioned as Steward in the Court Roll for 1818. He continued in this roll every year until 1852. The diaries confirm that he was the steward until at least 1861 and there is no reason to doubt that there was any break in his tenure, even though he fell out with the lord in 1842.Presumably the other court books have failed to survive.

In 1815 Rampisham was on the cusp of being finally inclosed. The open fields had long gone but there were extensive commons remaining to be inclosed. We will be exploring John Martin’s role in the Rampisham inclosure in the next section but in 1815 the villagers were still subject to the customary practices of the manor. They retained rights of common and which were to be swept away after inclosure. The court book begins in 1815 when the steward was one Thomas Clement [the name of the steward is not recorded in 1816 and 1817]. The 1815 entry is unique in that it is the only one held whilst the manor remained uninclosed and we can thus compare the Court’s activities pre- and post- inclosure.

Being a steward to a manor was a responsible job with considerable powers and great care in selecting a steward had to be taken by the lord “for if he be defective in any one of these three qualities, knowledge, trust or diligence, the lord may be much prejudiced.” The reason for the caution was that in the absence of the lord the steward could exercise almost exactly the same powers the lord.

Holding Court.

Courts Baron were usually held once a year. The court followed a set pattern which was detailed by Scroggs in 1728 [5] it is doubtful if the manner of conducting the court had changed significantly in hundreds of years. Since not every year in the court roll has entries of interest the following account of the Court at Rampisham has been compiled from entries over several years. Entries in text boxes are taken directly from the court roll, other quotes are from Scroggs.

On 20th November 1852 Martin travelled to Ransom and held the court in the Manor House. The court opened with a proclamation, [6] “Oyez [three times] All Manner of Persons that do Suit or Service to this Court Leet and Baron draw near and give your Attendance and answer every Man to his name”

Originally attendance at the Court Baron was restricted to free tenants but by the time we come to the 19th century all tenants were required to attend the court for they had an important part to play. Collectively they were known as the ‘Homage’ and a small number were appointed as juror’s to adjudicate on any problems that were brought to the attention of the court. After the proclamation came a declaration,

|

Liberty & Manor of Rampisham Dorset. A view of Frankpledge with the Court Baron of Susan Daniell Widow, George Daniell and John Hutchings Esq Trustees of the late John Daniell Esquire deceased late Lord of the said Manor held in and for the said Manor on Thursday 26th Day of October 1820 Before Mr John Martin Steward there. |

Here are words that echoed down the centuries, for the first line comes straight from medieval times. The declaration is interesting as it shows that Rampisham enjoyed the status of being a Liberty as well as a Manor. This is one of those archaic administrative divisions with which English history abounds. Anciently the King took to himself certain rights known as the ‘Jura Reglia’. Some of these rights included hunting and fishing over an area of ground but equally anciently these rights could be devolved to a local Lord of the manor to enjoy and administer; in which case the manor would become a Liberty. Oddly neither Hutchins or Boswell [7] lists Rampisham as a Liberty.

The ‘View of Frankpledge’ was a system whereby law and order was maintained in the parish. Originally associated with the Sheriff’s Tourn, all ‘free’ men over the age of twelve had to attend and swear an oath of fealty to the king as well as promising not to be a robber. Households were grouped into units of ten, known as a tithing [tything]. Each man in the tything had to obtain and show that he had the pledges of the nine other men that he was a good ,honest man for whom they would give their surety. One of the ten was then appointed the tything man whose job it was to raise the alarm if a crime was committed. [8]

After the declaration had been read out the officers of the manor for the previous year were called.

|

Constable John Wallis Tythingman Joseph Ellis Haywards John Lewis Samuel Gundry. |

The office of Constable was in historical terms much more recent than the tything man, having been instituted under the Statute of Winchester in 1285. Their remits were slightly different for Constables were intended to keep ‘watch and ward’. Ward was a day time activity and the constable had to keep an eye out to “apprehend rioters, and robbers on the highways”. Watch on the other hand was a night time activity “to apprehend all rogues, vagabonds, and night-walkers, and make them give an account of themselves”.[9]

There are no references to any of these people in the diary but there is one reference to a constable in the poor law records at Evershot. The Constable at Toller caught one Henry Cornick who was accused of being the father of a bastard in Evershot, although the family seems to have lived at Rampisham.

|

28th April 1821 |

Henry Cornick having been apprehended in Framptons bastardy, horse hire to Dorchester Constable at Toller’s expenses &c as pd magistrates allowance Stamps for note |

7s 6d 14s 1s ½ d |

The office of tythingman was extremely ancient, Blackstone [10] puts it back to the time of King Alfred. As the head of the tything he had to ensure that every member of the parish belonged to a tithing and he bore overall responsibility for its actions. As a group the tithing had to raise the hue and cry and pursue and hopefully capture felons and fugitives. This was a surprisingly effective technique, the fields in these days were generally full of people, and as Neeson [11] has noted voices carry a long way across open fields.

The tythingman had to present all crime arising in the tithing to the court and the range of misdemeanours to be reported was comprehensive; “All common nuisance are presentable and indictable in this court whether they are in Highways, Rivers, Common Bridges, Bawdy or other Disorderly Houses, Selling corrupt Victuals, or Exposing them to Sale…Keeping false Weights or Measures, Neglecting to hold a Fair or Market…Also all common Disturbers of the Peace may be here indicted as common Barrettors [12], common Scolds, Eaves-Droppers, Swearers,….dangerous and suspicious persons, as Rogues, Egyptians [presumably gypsies], Vagabonds &c and those who go Abroad by Night and sleep in the Day; and those who inordinately haunt Taverns having no visible Means to live by”.[13]

One final thing, each tything had to possess a working pair of stocks or bear a fine of £5. Just as the Court Baron was incidental to the Manor, so were the tything man and constable ‘incidental’ to the court leet. Not every manor had a Court Leet but if it did it had to have a tything man and constable: in modern terms we would say they were ‘statutory’ posts, inseparable from the court itself.

Whilst the Hayward was not incidental to the manor or the courts or anything else for that matter it would have been a very rare manor or parish who did not have one. His role appears to have varied over the centuries but was everywhere considered to be essential.

Walter of Henley [14] writing in the 13th century lists his roles and attributes: “The hayward ought to be an active and sharp man, for he must, early and late, look after and go round and keep the woods, corn, and meadows and other things belonging to his office… he ought to sow the lands, and be over the ploughers and harrowers at the time of each sowing. And he ought to make all the boon-tenants and customary-tenants who are bound and accustomed to come, do so, to do the work they ought to do. And in haytime he ought to be over the mowers, the making, the carrying, and in August assemble the reapers and the boon-tenants and the labourers and see that the corn be properly and cleanly gathered; and early and late watch so that nothing be stolen or eaten by beasts or spoilt.”

By the 19th century his role appears to have diminished and be combined with that of the ‘pinder’. The hayward was specifically tasked with maintenance of the hedge rows [the ring fence] as it was often called, whilst the pinder was tasked with ensuring that the animals were confined to the waste and grasslands. He had the power to impound animals and then charge a fee the ‘pinlock’ for their release.

Next the Foreman of the jury was required to swear an oath. The exact form at Rampisham is not known but Scrogg’s helpfully gives an example of the oath to be taken:

“You shall well and truly enquire, and true Presentment make of all such Articles, Matters, and Things, as shall be given you in Charge; the King’s Counsel your Companions, and your own, you shall keep secret and undisclosed. You shall present no Man for Envy, Hatred, or Malice, nor spare any Man for Fear, Favour, or Affection, or any Hope of Reward; but according to the best of your Knowledge, and the Information you shall receive, you shall present the Truth, the whole Truth, and nothing but the Truth. So help you God.”

After the Foreman had been sworn, the Jury for the year was then named and the main business of the court minuted.

|

Names of the Jury & Homage George Drewe Samuel Grundy John Peach Jonathan Grundy Peter Beater William Dunsford William Hallett James Combes Thomas Beater Luke Bridle John Wallis John Swatridge Samuel Squibb |

Local democracy was positively enforced in those days, as those who had not attended were named and shamed and then fined [15] on a scale befitting their social status.

|

First we present the Freeholders of this Manor who have not made their appearance here this day and are made default for which we amerce them 2s each Also we present the Leaseholders and Copyholders of this manor who have not made their appearance here this day and have made default for which we amerce them 1s each Also we present the Resiants [16] of this Manor who have not made their appearance here this day and have not been essigned for and have made default for which we amerce them 6d each. |

As it happens it would appear there weren’t any absentees for the year.

Next were named the manorial officers for the coming year. First came the officers of the Court Leet, the constable and tything man,

|

Also we present John Wallis to serve the Office of Constable and Robert Trim to serve the Office of Tythingman for the year ensuing and order that they or their sufficient deputies come into this court and take the oath of office before the rising thereof or go before one of his Majesty’s Justices of the Peace within ten days and take the said oath under the penalty of Five pounds making defaults Also we present John Lewis and Samuel Gundry to serve the office of Hay [sic] for the year ensuing |

As the Constable and Tythingman were officials of the King they had to be sworn in by the local justices of the peace. In Scrogg’s day this was set at £5 but by the 19th century it was set at £10 and the official record of their swearing can be found in the Quarter Sessions books for the county.

Next come the officers of the manor, usually called the haywards although at Rampisham referred to simply as ‘Hay’ and after they had been sworn the misdemeanours of the villagers were now announced by the Foreman of the Jury. In 1815 there were several miscreants,

|

“We present Joseph Ellis hath taken a piece of land part of the waste |

|

Also We present Mark Palmer hath taken a piece of land part of the waste”. |

By the 18th century the waste was coming under pressure from overstocking. It suited the inclosers to blame the poor for this although in reality it was only the larger farmers [and surprisingly butchers] who could afford large herds or flocks. It was not helped by diminution of the waste by a process known as assarting. Over the centuries the waste had been nibbled away at with new closes, or, as they were called assarts, being formed. This was technically theft as the waste land belonged to the lord of the manor. It may be a sign of the times but no penalty appear to have been attached to this, usually the perpetrator would be fined but given the imminence of the final inclosure award perhaps they were only taking in parts of the waste in anticipation of the award. We do not know.

|

“We present the Rector of Rampisham, his tenant, the occupier of John Daniell’s farm and the occupier of Yard farm hath no right to cut or carry away or burn any fuel or furze that shall grow out of the common of our parish in either their houses and we amerce each of them one guinea for every load they shall cut or carry away or burn in their respective houses” |

This indictment demonstrates the impartiality of the court for it indicts both the Rector and the Lord of the manor’s own tenant [unnamed]. They had been cutting furze [Gorse] from the common illegally. Furze was widely used as a fuel, the most famous furze cutter in literature probably being Clym Yeobright in Thomas Hardy’s Return of the Native. In a nod to the social status of those indicted the fines [amercements] were in guineas whereas for the commoners they were in shillings.

In 1815 the waste or common at Rampisham was finally inclosed extinguishing all rights of common. All of the entries in the court roll/ book were made after this event but we are very lucky because, before the award was legally enrolled at the quarter sessions, there was one final Court under the old regime. We are thus able to compare and contrast the workings of the court before and after inclosure.

After the miscreants had been named and shamed in the days before inclosure the customary rules and regulations of the manor were read out to remind the homage of their duties. Although we have only one record of the rules [from the 1815 court] we may assume they had not changed greatly over the years.

In the record from that year there appears to be no attempt to group similar rules together but I have taken the opportunity to do so,

|

“We present, no person shall carry away furze or fern from the Hill into any other parish to burn or make dung under penalty 20/s a Troad |

|

We present no furze cutter to have more than 2/6d a troad,” |

If some people were not allowed to take furze it follows that some were, but as these are not spelled out in the roll we must assume it was a right afforded to the cottagers in the manor. As such it was for personal use only and not intended for sale outside of the parish although presumably it could be sold within the parish. Many manors specified that products such as furze, rushes and so on had to be carried away on the backs of the men, they were not allowed to use horses. I have not been able to find out what a troad equates to but it is interesting that there was some form of price control in operation. Legally a right of common was the right to make a profit from the land of another person–it was just that it must not be too much profit.

|

“We present No person shall cut any peat or turf without the consent of the Lords of the Manor on Higher or Lower Common and that no person be permitted to cut more than 6,000 turves on any pretence whatsoever. |

|

We do appoint Sam Squibb John Goldring John Lewis and Emmanuel Squibb turf cutters and direct that no other person be permitted to cut turf and that no more than 1/6d per 1000 turfs be paid for cutting the same”. |

Turbary, the right to cut turf on the common, was widespread where turf was available. The court entries are not particularly helpful. The first clause seems to indicate that there was no general right of common but that under the second clause there was a licenced right for four men to cut the turf. This was probably a commercial enterprise although at 1s 6d per thousand it would only have netted them 36s, not a vast amount even in those days. So far so good but at the end of the roll we find the following:

|

“We present William Ellis, William Gundry, Joseph Gundry, Emmanuel Squibb, John Lewis, Charles Curtis, Henry Russell, John Hallet, William Green, John Roll, Joseph Ellis, John Swatridge, James Neale, William Soaper, Joseph Davis have lately illegally cut and carried away turf from Rampisham Hill and Rampisham Common without the consent of the Lords of the Manor and against standing presentments of the Jury and the Manor Court which offence is an infringement of the rights of the Lords of the Manor and also of the rights of tenants of the manor having common of pasture.” |

There are several interesting points about this. Firstly John Lewis and Emmanuel Squibb despite having been charged with illegally cutting turf were appointed earlier in the document as two of those who were to be entitled to cut the turf that year. It appears that crime did pay after all. Second the last line seems to indicate that there was a general right to the turf amongst commoners having the common of pasture. Finally the list of Jurors who signed the court roll included Samuel Squibb and Samuel Gundry who were presumably relatives of two of those who stood accused. No penalty appears to have been attached to their crime.

|

“We present John King to fund a gate, |

|

We present that if any persons fences against Kingcombe are out of repair that they repair them by Christmas next under penalty of 20s each neglect,” |

The open fields were never completely open, nor indeed was the waste or the grasslands. At their peripheries they were often ‘ring fenced’ to avoid stray animals ruining the cereal crops. Today food is so plentiful that we forget how precarious it’s supply was at one time. Allowing animals to damage growing crops was a heinous crime which was fined accordingly.

The word fence needs to be understood in its meaning of the time,“that which serves as a defence.”[17] Loudon in his Encyclopaedia of Agriculture noted four types of fence; ditches, walls, hedges and wooden constructions which ranged from two bar fences to hurdles. The former were of limited use in sheep country without some form of fill in and at inclosure it was not uncommon to use a three fold approach. A ditch was built within the new close that protected a hedge planted on the boundary with the next close. Many inclosure acts then allowed the hedge to be protected from the other side by the erection of a two bar wooden fence placed on the neighbours land. Typically this was allowed to remain for seven years by which time the hedge had become established and the fence could be removed. The costs of this were considerable, even a ditch and hedge were reckoned to cost 1/6d a yard. Had Thomas How managed his fences better doubtless his stallion would not have got in with Martin’s mare.

|

“We present Hook farm hath no right of sheep common over Hook way and that the occupier must keep a shepherd to follow his sheep to where they have a right to feed” |

This is a highly specific rule. The parish boundary between Rampisham and Hooke ran over the top of Rampisham Hill which in 1815 was a large area of waste. Hook farm can be identified on the tithe map and on the 6” OS [1888 -1913]map is shown as Hook Court near the centre of the village quite a way from Rampisham but the road out of Hook lead straight onto Rampisham Down. Parishes often shared commons or wastes like this and there were two ways of handling the situation. ‘Common Pur Cause De Vicinage’ was a mutual agreement between parishes to share a common waste. It avoided the problem of litigation that could result from trespass by the animals but in this case it is clear that ‘Hook way’ [wherever that might be precisely] was not covered by such arrangements.

|

“We present the occupier of every whole place in the Parish of Rampisham shall be entitled to 6 leazes for Horse or Bullocks to depasture on the Higher Hill and no more than 6 sheep and two yearling bullocks to be adjudged equal to one Horse or Bullock |

|

We present the occupier of every half place shall be entitled to stock the said Higher Hill in the same proportions not otherwise that nine small estates in the same parish shall be entitled to one leaze each for an Horse or Bullock Sheep or yearling in the same proportion not otherwise” |

By the 18th century many wastes had become overstocked and parishes responded by stinting [see below] and by restricting who could stock the common. This appears to be the response at Rampisham. In these rules we see spelled out the rights of common pasture over the waste. The conditions attaching to rights of common were as varied as the number of parishes and the people in them. They were always deemed to have existed since time immemorial but what ever the rights were, they were not totally immutable. Where over grazing was a problem, for instance, the number of animals the commoners were allowed to depasture on the common could be varied periodically. So long as the stint, as it was known, applied to all, and varied in proportion with the original right there was no legal issue. This can be seen in the above rules where the occupier of the ‘whole place’ had twice the right of a ‘half-place’ holder. What the rules do not state of course is what constituted a whole or a half place.

No general rule can be given over rights of common as practice varied from place to place. Occasionally such information is available by chance. The parish of Stratton was unusual in that it contained two manors, Stratton and Grimston[e] lying side by side. It was not inclosed until the early 20th century but had been extensively studied by a respected historian, Gilbert Slater.

He found that in both manors “The copyhold’s… were either “half-livings,” “livings,” or, in one or two cases, other fractions of a living. A half-living consisted of four or five nominal acres in each of the common fields, and common rights upon the meadow, common fields and common down, in Stratton, for one horse, two cows, and forty sheep. A whole living consisted of a share about twice as large in the field and meadow, and a common right for two horses, four cows, and eighty sheep.”[18]

It may seem slightly strange to talk in fractions of a living but this was not uncommon. A cottage might have a certain right of common attached to it; if it happened that the cottage was internally divided to make two cottages, or if it was demolished and two new cottages put up in its place the right would be divided accordingly.

Prior to 1290 AD the common of pasture [the right to graze] animals on the common was limited to those animals, horses or cattle, which were termed ‘levant and couchant’; that is the right was limited to those few animals which could be maintained throughout the winter on the land which the tenant held. This probably explains why the horse and cattle leazes are the same in both manors. After 1290 AD the right of common was extended and could now include sheep. The manor of Stratton was much larger than that at Rampisham which probably explains the difference in numbers that could be stocked.

|

We present No parishioner shall run any bull or steer on Lower Common on penalty 5s each |

There were several component parts to Rampisham Common and it is not clear which part was the ‘Lower Common’. One of the criticisms of open commons was the fact that the breeding of animals could not be regulated. One answer, which was very common, was for a reputable person such as the local rector or the Lord of the Manor to provide one of proven quality. This does not explain though why a steer [neutered male calf] should not be allowed to graze there.

|

We do agree to stock the common on 10th October instead of Old Lukestide |

St Luke’s day is the 18th October and St Lukestide was the day before. Why the day was changed is not known.

|

We present no person being an out parishioner and taking a lease or leases in the higher common shall have any right to run the same stock on the lower common after Lukestide on penalty 5s each, We present no parishioners shall put horse or mare in the lower common after Lukestide |

Many parishes actively forbade the stocking of the common by people who did not live in the parish. Mere possession of a right of common did not mean that the owner was always in a position to take full advantage of them. Not every commoner at Rampisham [or elsewhere for that matter] could afford their full quota of beasts, and would sometimes take in stock for out parishioners – a process known as agistment and many manors had rules forbidding it, although not seemingly at Rampisham. Similarly if the owner of a right of common pasture did not wish to take up his options he could lease them in their entirety. This rule however goes a little further than regulating this. One of the dubious tricks that the larger landowners would sometimes play would be to turn out group of cows out on the common in the morning, take them off in the afternoon and replace them with a second set of what one must assume were hungrier cows. This was usually solved by having a cowherd who collected all the cattle from their owners in the morning and returned them in the evening. This rule appears to be designed to prevent a variation on that theme.

|

We present every person turning horned cattle or horses into the commons do mark them on horn or hoof with a burning iron with the letters of their names and do agree that the cattle be registered with the Haywards under penalty 20s |

Here is another rule designed to prevent overstocking. In some areas the commons were prone to overgrazing by cattle from neighbouring parishes or by passing drovers and branding was a common method of separating the intruders. Some parishes had their own ‘town’ brand as well as the owners mark.

|

We present no person to keep pigs or geese on common road under 5s penalty, |

Pigs and geese were popular animals for the commoners to keep. Pigs had to be ringed through the nose so that they could not use their snouts to grub up the ground.

Finally a reminder that people who had no rights of common pasture were not allowed to keep animals on the common.

|

We present no Horse Mare or Bullock shall be found on the Hill or Common of said Parish belonging to any person who hath no lawful right to the same every such person shall forfeit 10s 6d for every Horse Mare or Bullock so found. |

After inclosure all these customary rules were swept away and in the following years the rules were much reduced. From 1816 after the investiture of the manorial officers etc. the following rules are recited,

|

Also we present and order that no person or persons shall suffer their cattle to feed or go about the Drove lanes or Highways with or without follower if they do at any time we order the Haywards to impound them and take 6d for each Horse, Cow, Pig or other beast not exceeding three of each man’s stock and 6/d a score for sheep or under and two pence for turning the Key when stock is impounded by other person |

|

Also we present and order that no person or persons shall suffer their cattle to feed or go about the Drove lanes or Highways with or without follower if they do at any time we order the Haywards to impound them and take 6d for each Horse, Cow, Pig or other beast not exceeding three of each man’s stock and 6/d a score for sheep or under and two pence for turning the Key when stock is impounded by other person |

And that was that. After inclosure the common had gone and so had all the rules. There were to be no more furze or turf cutters, place owners, no more bulls, no more lessees from outside of the parish, no trespass by Hook farm – no common from which assarts could be taken. In the old days the cattle might, if tethered, have been allowed to graze on the edges of the roads – now even that was forbidden.

Another of the duties of the court was to maintain the list of customary tenants and to admit new lives to the copyhold. It was in this regard that Martha Best Bartlett fell foul of the court. Copyhold was a form of perpetual leasehold. The tenancy was held on [usually] three lives. If one of the people named died another could be added. The terms of the tenancy depended on the custom of the manor but those customs were protected under common law and unless a tenant surrendered their tenancy they had an automatic right to have another life added. This was regulated by the manor court in a formal process of surrender and admission.

When preparing his Board of Agriculture report in 1812 Stevenson noted that increasingly tenancies that were surrendered were not renewed; “The copyhold tenures in this country are now become very few, owing, it is presumed, in a great measure to the frauds practised on the respective lords of manors, by the customary tenants marrying in the last stage of decrepid [sic] old age to very young girls, by which, according to the custom of copyhold tenures in this county, the widow is entitled to her free bench on the husband’s copyhold.” If a copyhold tenancy became vacant and there were none in the family who could or wanted to take it on then the copyhold would be extinguished and the tenancy would be replaced by a leasehold.

At the 1820 court one of the tenants is reported to have died but there is no mention of a replacement and it is not known if the copyhold survived.

|

Also we present the death of John Botten whose life was upon an estate called Coombes or Bicknells belonging to Henry Stickland since the last court |

The process of surrender and admittance is seen in the court baron held on Monday 2nd November 1818 when John Martin first took up his post as Steward.

|

To this court came George Dawe of Rampisham aforesaid Yeoman by virtue of Power of Attorney made by John Flood of Rampisham aforesaid bearing date 22nd June which was in the year of our Lord 1818 which said John Flood claimed to hold for the lives of John Wallis, William Wallis and John Wallis the younger by court roll of said manor bearing date 12th day of October in the year of our Lord 1805 the Moiety of one cottage with the appurtenances within the Manor aforesaid containing four acres of meadow land and one acre more at East Hill formerly in possession of Thomas Sturmy and afterwards the Revd. John Gatehouse |

John Flood was a copyholder in the manor who appears to have fallen on hard times and he is about to surrender his tenancy. Born in 1750 he had earned his living as a leather dresser. He appears in the diaries in 1832 when he was in distress again [he was 82 yr’s by that time after all] and was to die in 1837.The first part of the record reveals that John Flood held his land not on his own life but that of three others. Tenants giving up their tenures had to surrender them to the lord of the manor ‘to the intent that the lord might do his will therewith’. AccordinglyFlood [or rather his representative Dawe]

|

in full and open court surrendered into the hands of said Lord of the Manor the moiety of the said cottage aforesaid with the appurtenances and all the Estate Right Title Interest Claim and Demand whatsoever of him the said John Flood of and in the premises aforesaid to the intent that the Lord might do his will therewith |

On this occasion however the copyhold was to continue and the new tenant was John Jennings.

|

Whereupon at this same court John Jennings of Evershot in the county aforesaid Attorney at Law under and by virtue of the said power of attorney and took of the Lord aforesaid by delivery of the Steward the said moiety of one cottage with appurtenances [etc.] which was now surrendered / all Timber trees Heyres [sic] and other trees excepted / to have and to hold the said cottage [etc.] to the said John Jennings for and during the lives of the said John Wallis, William Wallis and John Wallis the younger, at the life of the youngest liver [sic] of them at the will of the Lord according to the custom of said Manor |

Note how the timber on the land were explicitly excluded from the tenancy, remaining in the ownership of the lord of the manor. The customs of the manor are then spelled out, first there was an annual rent

|

by the yearly charge of 2s 8d by two equal payments in the year that is to say The Feasts of the Annunciation of the blessed Virgin Mary and St Michael the Archangel [19]” In addition in the event of the death of one of the tenants ““and for a Heriot when it shall happen 5s and by all other works, Burthens, Customs suits and services therefore due and of right accustomed |

Jennings paid a ‘competent sum of money’ to Flood and then next, archaically but vital to the legality of the process Jennings had to swear an oath of fealty to the lord.

|

and for such an estate so had and granted the said John Jennings hath given to the said John Flood a competent sum of money and was admitted Tenant thereof and did his fealty to the Lord. |

The court records become much shorter after 1816 and some years contain very little ; the records below come from 1820. Oddly despite the parish having been inclosed small amounts of waste remained;

|

Also we present that Ann Knight has taken in part of the waste near Row Bridge |

|

Also we present that Jonas Stiles Snr. and Jonas Stiles Jnr. have not made their appearance there this day at which we amerce them 6/8d each |

Who the Stiles were is not known but their fines are not the standard fines mentioned earlier.

The stocks were to be a recurring problem, it is not known where they were kept in the village, though I suspect they were where the sign post is in the photograph.

Thomas Rowlandson again courtesy of the Met Museum of Art New York. Although very stylised it’s easy to forget that the clothing is probably typical of John Martin’s early life at least.

|

Also we present the stocks to be out of repair and order the same to be repaired within 21 days from the date thereof under penalty of one pound |

Finally we see the responsibility laid upon the hayward,

|

Also we present that if the Hayward at anytime after notice having been given to them [or at any time] neglect to impound cattle when upon the Roads or Highway shall be fined 6/s each |

This concluded business and at the end of the roll are the signatures of the jury which ended the court.

|

Signed George Drewe Samuel Grundy John Peach Jonathan Grundy Peter Beater William Dunsford William Hallett James Combes Thomas Beater Luke Bridle John Wallis John Swatridge Samuel Squibb |

John Martin was to remain the Steward at Rampisham until at least 1852 when the Court book ceases but he probably remained for a lot longer. For all these years there is little variation in the entries moreover the effectiveness of the Court Leet must be questioned for in the following years few if any of the problems noted below were actually resolved.

|

1821 |

Apart from a change of village officers the minutes are essentially the same as in 1820. The encroachment on the waste by Ann Knight mentioned above persists with no action having been taken. |

|

1822 |

The next year one Thomas Rogers has taken waste near the same place as Ann Knight, Row Bridge. |

|

1823 |

The encroachments persist nothing having been done about them |

|

1824 |

Ditto |

|

1825 |

The parish pound is out of repair and has to be repaired. Usually the job of the Hayward. |

|

1829 |

A new problem and one that is potentially more serious, for a public right of way has been blocked up, worse still it was after the rate payers had just paid for it to be repaired; “and we present John Allen Pope having thrown banks across the Hartgate Road leading to Kingcombe and ploughed up the said road [after having been stoned at the expense of the Parish] and converted it to his own use that the same is considered a nuisance to the Kings subjects” |

|

1830 and 1831 |

Exactly the same complaint about Pope [and in the same words] is made, nothing having been done to resolve the issue. |

|

1832 |

Now the ploughed up area has been turned into a plantation by the planting of fir trees. In the same year “a cottage and outhouses belonging to a tenement in possession of the Representatives of late Sam Squibb called Conways to be out of repair and order the same to be immediately repaired.” |

|

1833 |

Some ten years on, Thomas Rogers has now agreed to pay 1d a year [sic] for his encroachment on the waste. There is no mention of Ann Knight’s encroachment. John Popes ploughing up the road has paid dividends as the fir trees have grown and “have now become a complete hindrance to the public traveller” |

|

1834 |

The Hartgate road is still a complete hindrance but blocking roads seems to be catching as now a ‘drift way’ or drove road for cattle has been blocked up by John Stoadley and Robert Ivey who were ordered to remove it or face a fine of 20s. |

|

1836 |

Once again the stocks are in disrepair. Crime clearly pays as Robert Ivey has now been made Bailiff his previous misdemeanour clearly not being a block to public office. |

|

1838 |

The parish pound is out of repair again “We Present the parish pound out of repair 20s to amerced if not repaired by the Lord of the Manor” |

|

1841 |

Three years later it still out of repair and the fine has gone up. “We present the manor pound to be out of repair and order that same to be repaired by the Lord of the Manor under penalty 40s by default” |

|

1841 |

Robert Ivey has now been appointed constable. |

|

1845 |

Now the Rector is in trouble. “We Present that two bridges and the parsonage house in this parish are out of repair belonging to the Glebe” |

|

1846 |

“We Present Thomas Thorne’s house to be out of repair and order and the same to be put in repair within three months of the date hereof under penalty 40s” |

|

1846 |

Thomas Pope [? a relative of John Pope] has “stopt up a public footpath leading off Turnpike Road on Rampisham Hill towards Kingcombe”. |

|

1847 |

Thomas Thorne was presented as dead in 1847. |

|

1850 |

“We present the Dwelling house and outbuildings of a tenement called Lawmans held by William Beater Senior for his life under the Lord of the manor to be in a dilapidated state and order the same to be repaired within 6 months from date hereafter under forfeiture of the said tenement” One of the Jury signatories was William Beater ; probably the commonest reason for dilapidations like this was simply the age of the inhabitant. |

|

1852 |

The Court Roll ends with none of these issues seemingly resolved. |

This ends the record of Martin’s years as Steward of Rampisham but as well as a tenant of lands in Evershot he was of course subject to the Court Leet and Baron at Evershot and here too the Manor court survived into the later part of the century. He mentions the court at Evershot on three occasions but never gives any details and between 1827 and 1852 he does not mention it at all. Perhaps he was too busy to attend. Despite his roll as Steward he appears to be quite proud of his roll as foreman at Evershot ; why else record the fact ?

|

25th October 1852 |

Evershot Court Dined at Acorn – I was foreman of the Jury Expenses at the Court 18s |

Previous The Manor of Rampisham

In depth The Manorial Courts A simple guide to land tenures

1 Neeson ibid

2 Court in this context meaning ‘a formal assembly’ rather than a judicial court.

3 Scroggs W The Practice of Courts Leet and Courts Baron published at the Savoy 1728

5 Scroggs ibid

6 Text in boxes indicates actual text in the court roll. Un-boxed text indicates what was said, according to Scrogg’s but not recorded.

7 Boswell Civil Divisions of the County of Dorset 1833

8 Not to be confused with the tythingman who valued and collected the tithe.

9 Blackstone Commentaries on the Laws of England 1765 – 1769

10 Blackstone ibid

11Neeson J M Commoners: Common Right, Enclosure and Social Change in England 1700-1820.

12 A “common Barrettor is he who is eyther a common mover and stirrer up [or mainteyner] of suits in Law in any Court or else of quarrels in the Countrey.” Michael Dalton The Country Justice 1630

13 Scrogg’s ibid.

14 Walter of Henley Husbandry 13th century but precise date unknown.

15 Although oddly they were not recorded in the court roll.

16 Residents

17 Etymology dictionary on line.

18 Slater, Gilbert The English peasantry and the enclosure of common fields 1907

19 Both celebrated on 25th March also known as “Ladyday”.