A history of the commons: the courts.

Debates over the historical origins of rights of common were one thing but the legal system had to take a pragmatic view of their legal status and that view had to confirm to their wider understanding of the law. Thus it came to be believed that whatever their origin they had always been made by a specific grant or gift from the lord to his tenant.

Rights of common were both universal and particular; one form of right, common of pasture appendant [COPA] was so important that for the ‘necessity of the thing’ it, and the terms that it operated under, became universal to all manors and in time became a part of the common law. Other “appurtenant” rights, whilst being found in many manors, had terms which were particular to those manors. If, as the jurists believed, rights of common had arisen from specific grants then the question arises as to where and how those grants were made. As to where they were granted this is not a question that I have seen addressed in any of the literature but in this writers opinion, it would seem that the only place they could have been granted was in the Court Baron [see below] or Customary court of the manor. There are objections to this idea but in the absence of a suitable alternative we must assume it to be here that grants were made.

For Blackstone and the other jurists the Court Baron was a feudal invention of the Normans but if the Anglo-Saxons had been the first to grant the right where had they done so? Halsbury says that the Court Baron [see below] developed from the Anglo-Saxon ‘Hallmote’ but this is saying little more than that there was a meeting in a hall and is not a term that I have found used anywhere else. Similarly references to a ‘folcgemote’ in the law books of the earliest English Kings is generally translated as public meeting. It does not point to a meeting exclusively for the benefit of the occupants of a particular manor; in any case neither term sheds any light on the workings of such a court if it had existed.

The court of the feudal manor was the Court Baron [for the free tenants of the manor] and what was called a Customary court for the villeins. Since, as we will see, there were few free tenants at the time of Domesday, but lots of villeins, the customary court must have preceded the Court Baron. [1] For the jurists however the manorial courts began with Court Baron and their texts are silent on what must logically have preceded them.

The role of the Court Baron was described by Sir William Scroggs [2] in 1728, at a time when there were still large numbers of functioning manors in the country . The Court met regularly [3] and was attended by the ‘Homage’, the free and [4] unfree tenants of the manor. The Homage was not only the body of tenants who attended the court but the oath that they had to swear to the lord when they were admitted to the tenancy. An oath of fealty was slightly different as it was simply a pledge to be faithful to the lord [i.e. honest]; in contrast the oath of homage was a direct acknowledgement that the tenant owed their land holdings to a grant from the lord of the manor and that some service was due from them in exchange.[5]

Decisions about the manor were made in the Court Baron and the logic is that the granting of rights of common stemmed from the same place and yet nowhere have I seen this said. Even texts on copyhold tenancies, which were grants of land that were almost always associated with rights of common, make no mention of them. Furthermore Scroggs makes no mention of them even though at the time he was writing it was still possible for the lord to grant new rights.

How they were granted is another matter. Written records seem to have been kept to a minimum. Part of the work of the court was to keep records of the various tenancies and any admissions or surrenders of the customary tenancies. Scroggs for example recites the procedure to be followed on the admission of a new tenant of the manor;

“I admit you Tenant to the Premisses (that is to say) to one Messuage, &c. and this is to hold to you and your Heirs at the Will of the Lord, by the Rents, Customs, and Services therefore due and accustomed; you paying your Fine, and performing your Suits and Services”.

One problem that may be encountered is that record keeping, and perhaps more importantly, the survival of records appears to be rather patchy. Court rolls were the minutes of a particular meeting and it would have been unreasonable for them to have had to detail all the customs and practices of a manor on each occasion. Whether there was a separate central record of these or whether they were simply propagated by word of mouth from generation to generation I cannot say. That the details must have been known to the commoners is evidenced by the fact that the homage was supposed to report anyone in the manor abusing their rights, or indeed using the common without any rights at all. By the 19th century the Court Baron in many parishes was a shadow of its former self, if indeed it had survived at all. Inclosure of the manor effectively abolished many of the Court’s functions. The distinction is clear when we consider the records of the Court at Rampisham before, and after, it’s common was finally inclosed in 1815. [ See https://johnmartinofevershot.org/rampisham-courts-baron-leet ].

A glance at virtually any parish in Hutchins [6] reveals a bewildering array of owners, tenures, grants, incidents, services, fines, fees and so on and so forth. In most manors, the commoners knew their rights, or thought they did; centuries of exercising them had got into their DNA and if there were any question over what they were they could always raise the issue at the Court Baron – couldn’t they? Well yes and no. If the matter could not be resolved in the Court Baron then there was always recourse to the courts and it’s during the Tudor/ Elizabethan period that there was an explosion cases coming to the courts which stimulated the interest later of jurists like Sir Edward Coke. It was left to the judges to make sense out of a complex situation. In arriving at their judgements they inevitably reflected the broader concerns of their society with its overarching desire to preserve an individuals property rights.[7] In making the law however they also created a particular version of history. It suited Elizabethan society for example to believe that common rights originated in every case from specific grants made by the lord of the manor. It was this that caused one Victorian author, Kenelm Edward Digby, to say that the rights of common, as that society had come to know them, were nothing more than ‘the invention of Elizabethan lawyers’.

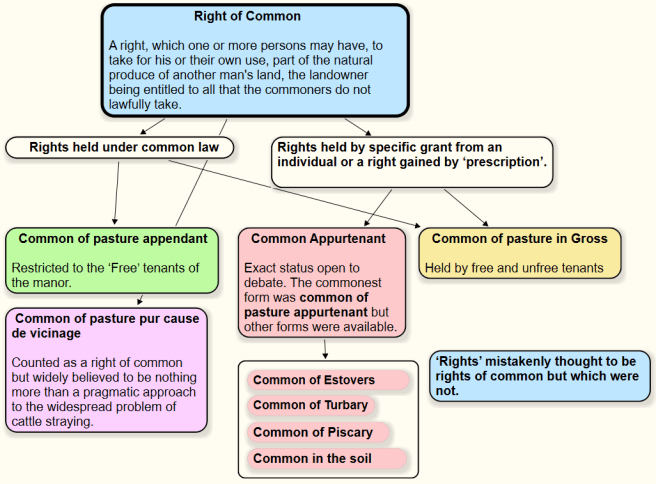

As we will see in a later post it was not always easy to decide who was, or was not a commoner but another problem that had to be dealt with was the question of what customs and practices constituted a right of common. Taking turf for heating, for example, could be a right of common but if it was what were the rules governing it? How much turf could be taken? Could it be sold on? An early task of the jurist then was to answer questions like these but by the 19th century a range of rights of common had been codified and the graphic below gives an outline of the rights.

We will have more to say about each individual right later but the overall picture is one of four types of right. On the left is a single right known as ‘Common of pasture appendant’. Considered to be the most ancient of all the rights it was eventually to become what was known as a ‘common law’ right. Its scope was strictly limited to grazing.

To its right are a series of ‘commons’ which were grouped together and said to be ‘rights of common appurtenant’. Their legal status was different to the common of pasture appendant and covered not only pasturing but other rights on the waste. Finally there are two rights, ‘common of pasture in gross’, and ‘common of pasture pur cause de vicinage’ which did not fall into either category and which for a variety of reasons some lawyers thought were not rights of common at all but which had come to be regarded as such by the courts.

Finally there were a whole range of rights that appeared to be of common right but were not. Gleaning, the use of the wayside verges to graze, various ‘rites’ associated with the hay and corn harvest for example were often thought to be a ‘right’ belonging to the poor who were so often disabused when the parish was inclosed. Such a neat classification is a convenient fiction. The distinction between the various types of right was never so clear as this as we will see. It was an attempt to provide round holes for the many square pegs that existed but for the moment it will serve to give an introduction to the subject.

The next three posts will look at the land to which rights of common attached.

[1] CUSTOMARY COURT: The deliberations of the court were written on parchment that were then curled up and stored – the court roll. The first mention of a court roll, not the actual roll itself, appears in the ‘Year Book’ of Edward 3 in 1369 but this was a century after the first mention of a right of common [1275] so that some sort of Court had existed long before this time but no records have survived from before this time and so we do not know precisely when they were established.

[2] ROLE OF THE COURT BARON: The Practice of Court Leets and Courts Baron ….published from the manuscripts of Sir Will Scroggs 1728.

[3] REGULARLY: Intervals varied with time. In Scroggs’s day it was supposed to be at least every three weeks. In the 19th century it was usually once a year.

[4] FREE TENANT: Free tenants of the manor held their land by free service and would, in time, become the equivalent of the modern freeholder owning their land outright without service being due the lord. However a free tenant of the manor was still expected to pay homage to the lord and in theory at least could not exercise his right of common unless he did so.

[5] HOMAGE: The oath of Homage was along these lines “humbly kneeling and holding up his hands together between those of his lord, he professed that “he did become his man, from that day forth, of life and limb, and earthly honour ” ; and then he received a kiss from his lord, a ceremony which still forms part of the English coronation service”. Hone 1906

The Unfree tenants were under no doubt as to the obligation they owed the lord for their lands but in later centuries swore much the same oath.

[6] HUTCHINS: The History and Antiquities of the County of Dorset , John Hutchins 1784

[7] The cynic would say there desire was to preserve the property rights of the right kind of people’s rights, not necessarily all people’s rights.

Categories: In Depth