With all this academic talk of common rights it is worth remembering that on an every day basis they went by and large unremarked. This was a world where everyone knew everyone else and where minor infringements of rights were either tolerated or the cause of lifelong enmity.

Officially the Court Baron was the place to decide disputes over rights of common and at one time this would have been enough. Unfortunately we are often hampered by the paucity of records that survive and this lack of records may even have been a problem to the lords of the manor themselves. The growth of manorial surveying in the 16th and 17th may have been a result of a keen marketing strategy on the part of a new breed of land surveyors but it may equally have been a consequence of the fact that many lords no longer knew precisely who held what land or on what terms. They wanted to take stock – a traditional terrier served this need but when accompanied by an attractive and impressive map how could they resist. After all who doesn’t love a map? The most famous of all these is Mark Pierce’s survey of 1635 from Laxton in Nottinghamshire and surveys such as these are often revealing when the court rolls are absent.

Closer to home than Laxton we have one map and one record of a Court Baron at Rampisham before it’s enclosure in 1815 and two manorial surveys from Child Okeford.

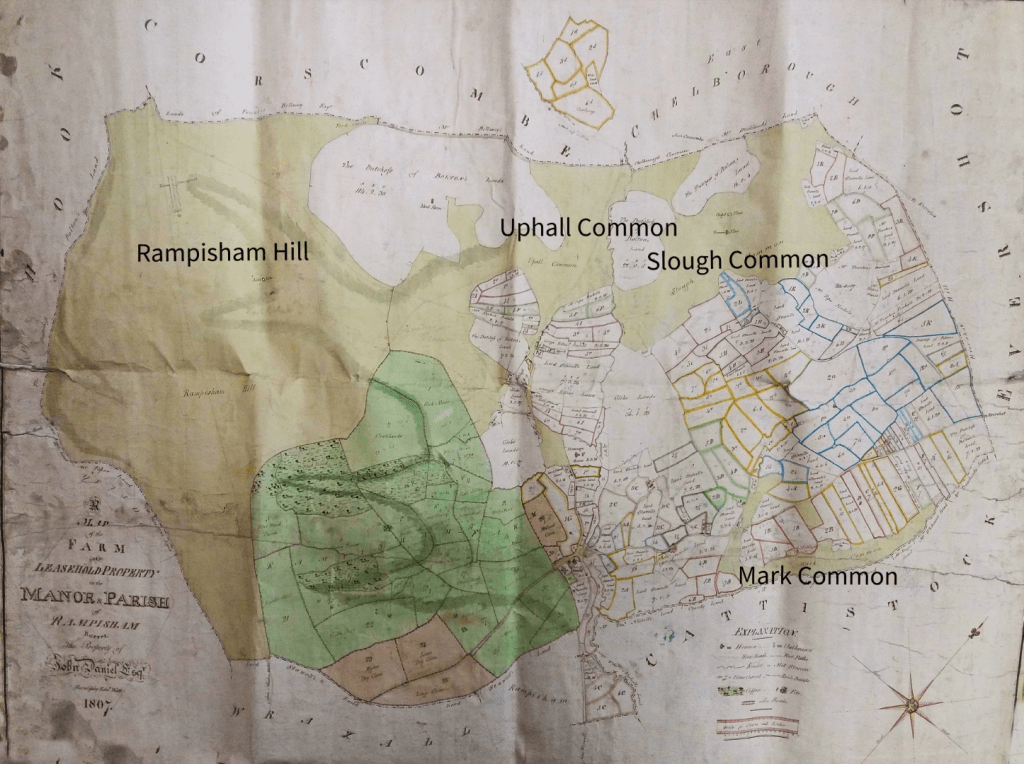

This map below is of the manor as it was in 1807. It was surveyed by Edward Watts, a surveyor from Yeovil, with whom John Martin worked occasionally. It shows the manor pre-inclosure and as can be seen extensive wastes still existed. There had been several major encroachments on it over the years, the dark green area was almost certainly part of the original waste and Rampisham Hill, Uphall and Slough Commons were almost certainly contiguous at one time. By 1807 however there appears to be a fence separating the Hill from Uphall and Slough whilst a tributary of the River From divides Uphall and Slough.

The full extent of the waste must at one time have amounted to nearly half the area of the manor [2030 acres at tithe commutation] emphasising it’s importance to the village but also the fact that it would have been difficult for the “1 slave; 10 villagers and 6 smallholders [1]” found in Domesday to have farmed it all.

To see the working of the Court Baron I have only been able to find one record made in 1815 before the enrolment of the Inclosure act. The first entry of relevance relates to common of pasturage on a part of the waste known as the higher hill which I presume to be Rampisham Hill itself.

| “We present the occupier of every whole place in the Parish of Rampisham shall be entitled to 6 leazes for Horse or Bullocks to depasture on the Higher Hill and no more than 6 sheep and two yearling bullocks to be adjudged equal to one Horse or Bullock”. |

Whether this was an appendant or appurtenant right is not known but given the lack of freemen in Dorset before Quia Emptores it is probably an appurtenant right. Although the practical details of management varied from manor to manor there do seem to be some general principles and these were illustrated by the historian Gilbert Slater when he studied what was probably the last inclosure in Dorset at Stratton and Grimston[e] [2].

Note the reference to ‘the occupier of every whole place’ in the Rampisham entry, Slater found a similar thing at Stratton and Grimstone although there the tenants occupied ‘Livings’ rather than ‘whole places’. “The copyhold’s… were either “half-livings,” “livings,” or, in one or two cases, other fractions of a living. A half-living consisted of four or five nominal acres in each of the common fields, and common rights upon the meadow, common fields and common down, in Stratton, for one horse, two cows, and forty sheep. A whole living consisted of a share about twice as large in the field and meadow, and a common right for two horses, four cows, and eighty sheep.”

This was a ‘full’ inclosure as the open fields still existed and there is a clear link between the area of land held and the extent of the right. He also mentions that there were rights attached to the possession of cottages but does not indicate the extent of these rights.

At Stratton and Grimstone then a particular area of land in the open arable fields got you a standard set of rights; ten acres got you two horses, four cows and so on. At Rampisham the situation was slightly different although in essence the system was the same. Indeed a ‘living’ at Stratton and Grimstone was, in the court documents, also referred to as a ‘place’ so it comes as no surprise to see that at Rampisham there were whole places, half places and so on.

There were differences between the three manors. Firstly the 1815 inclosure at Rampisham was of the commons only. Mr Watt’s map from 1807 shows that with the exception of one or two isolated strips there were no open arable fields left. It is presumed therefore that each ‘place’ was an area of any land held in the manor, whether it was arable or pasture. Even if this was the case it is not known how much land constituted a whole place. Each ‘place’ got you six’ leazes’ [3] and each leaze had a numerical unit of animals attached to it. Although we are told that six sheep were equivalent to one horse or bullock there is no mention in this entry as to how many horses or bullocks were attached to one leaze. Further down the court roll though we learn that, as at Stratton and Grimstone there were degrees of right, and that one leaze was for one horse or one bullock or one sheep.

| “We present the occupier of every half place shall be entitled to stock the said Higher Hill in the same proportions not otherwise that nine small estates in the same parish shall be entitled to one leaze each for an Horse or Bullock or Sheep or yearling in the same proportion not otherwise”. |

Note the types of animals that could be grazed is limited to animals levant et couchant. This was of course a feature of COPA but it would be a mistake to imagine that just because COPR could allow other species to be be grazed on the waste that they were. I am sure that many COPR were restricted to these animals just as they were in COPA.

In so far as other rights are concerned, there weren’t any. As we will see later just because a particular type of right could exist it is not automatically the case that it did exist. There was a right of common of turbary for example which allowed turf to be removed but just because a right could exist it must not be assumed that it did exist. As we will see when turf was removed at Rampisham it was not covered by a right of turbary.

The rolls occasionally tell us what is not allowed.

| “We present Hook farm hath no right of sheep common over Hook way and that the occupier must keep a shepherd to follow his sheep to where they have a right to feed” |

The boundary between Rampisham and Hooke ran over the top of Rampisham Hill which in 1815 was a large area of waste. Hook farm can be identified on the tithe map and on the 6” OS [1888 -1913]map is shown as Hook Court near the centre of the village quite a way from Rampisham but the road out of Hook lead straight onto Rampisham Hill. Parishes often shared commons or wastes like this and between manors ‘Common Pur Cause De Vicinage’ often existed. This was a mutual agreement between neighbouring manors to share a common waste. It avoided the problem of litigation that could result from trespass by the animals but it was not an option open to a farm held in severalty and a neighbouring waste held in common.

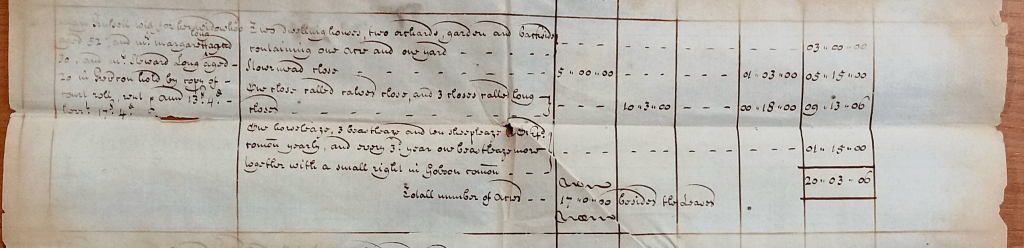

Now we turn to Child Okeford. Here although some court rolls survive for the manor of Child Okeford Inferior they are not instructive. Luckily fragments of a manorial survey made in 1726 survive which throws some light on the situation there. It was made for Thomas Haysome a merchant of Weymouth who had just bought the manor. A crop of this is shown below.

The original is very frail and faded. This particular entry reads,

“Mary Penfold [?] has for her widowhood aged 52 and Mary Longard 30 and Stewart Longard 20 in [reversion??] hold by copy of court roll rent p[er] ann[um] 13s 4d heriot [??] 17s 4d

Two dwelling houses, two orchards, garden and #### containing one acre and one yard Stour mead close 5 acres [of meadow.]

One close called calves close and 3 closes called long close 10 acres 3 rood [pasture]

One horse leaze, 3 beast leaze and ten sheepleaze yearly home comon and every 3 year one beast leaze now with a small right in Gobson common”

Here we have a complete listing of Mary’s holdings. A seperate and later court entry for the same manor [by then owned by Henry Seymer] tells us that in the manor widows had a ‘right of free bench’. This meant that Mary took over her husband’s tenancy when he died without having to pay for the privilege. The other two names on the copyhold are presumably brother and sister although what relation they have to Mary is not known. It is often said that married women could not own property. This was true enough for ‘personal’ property such as money, jewellery and the light but not for ‘real’ property – land- which they could retain if they chose to.

Mary own’s ‘closes’ or inclosed parcels of land and the manor had partially enclosed probably in the 17th century. These closes could have been formed from old arable lands, in which case these rights could have been COPA but the rights described for Gobson Common were almost certainly not. Gobson Common was [and the area still is] an isolated and detached part of the parish which was added to Child Okeford in 1601. It is not known to which manor it had belonged to originally because the owners, the Capel family, had lands all about the area. This right therefore must have been a COPR granted probably granted around that time.

Unfortunately insufficient of the survey survives to be able to say much more than this although it seems that Child Okeford was not as generous as at Stratton and Grimstone. There a holding of ten acres allowed you to graze two horses, four cows, and eighty sheep in Child Okeford a holding of some fifteen acres was worth one horse three cows and ten sheep. Note too that she had an extra ‘beast leaze now with a small right in Gobson common’ every third year. What on earth this was or how it arose is anybodies guess. More over it was not the only example of a right of common which seemed to have no logical basis.

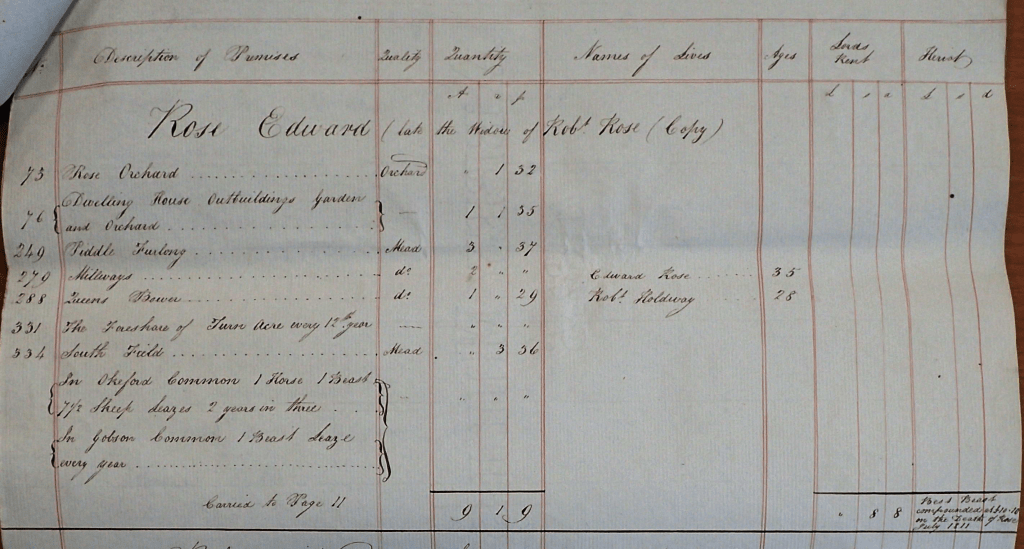

There were two manors in Child Okeford and in 1826 the other manor was surveyed and below is a crop for an entry for Edward Rose. Rose was probably the son of ‘the widow of Robert Rose’ who was his father and the tenure was copyhold for lives. His mother may have had the free bench use of the tenancy and he had inherited some nine and a half acres in the main part of the village. He had a variety of rights and these just go to illustrate how complicated matters could be. The first right was ‘the foreshare of twin acre every 12th year’. This meant he was able to take the hay from a small meadow [identifiable next to its twin on the tithe map] but why this was only every 12th year, or what practical value it had for him, is difficult to say. No mention is made of the right to graze on the aftermath once the hay had been cleared away.

In the home common he had rights amounting to one horse, one cow and seven and a half sheep leazes for two years out of three. What happened in the third year is not stated. The rights may have been common appendant which would explain the rather curious idea of stocking seven and a half sheep on the common. Rose holds no arable land in the parish but it is possible that this had been converted to meadow land after an early enclosure. In this case so long as the meadow could be converted back to arable the right was not extinguished. COPA was partible which means that the original holding may have been for fifteen sheep, two horses and two cows. If half the arable land had been sold then the number of sheep would have been halved to give this curious notion. This does not explain however why it was only for two years in three.

Rose held no land in Gobson Common but still had a beast leaze there every year. The area of Gobson Common was some ninety three acres with a population living on it of just seven households. It appear to have been used as a sort of overflow for grazing livestock perhaps to avoid overstocking of the home common.

The rent for this land was even then a trivial 8s 8d and had not changed since the inception of the copyhold. Strict rules governed copyhold tenures one of which was that the rent could not vary or the copyhold would have ceased to exist. The admission ‘fine’ [4] is not mentioned but Rose’s heriot is. A heriot was typically paid on the death of the lord of the manor or the tenant. It was usually the old tenant’s ‘best beast’ but in Rose’s case a monetary payment was due instead.

Even the legal text books sometime had a difficult time categorising rights of common. There was as many variations on a theme as there were manors and parishes and these examples from Rampisham, Stratton & Grimstone and Child Okeford illustrate just a few of them. They are solely concerned with common of pasture, the right which was found in all manors where the open field system had once held sway. In the next post we will consider the other rights that could exist within a manor.

[1] 1 SLAVE, 10 VILLAGERS and 6 SMALLHOLDERS: Domesday refers not to individuals but households. The usual multiple to arrive at the population is around 4.5 people per household with the exception of slaves who were deemed not to have any families.

[2] STRATTON AND GRIMSTONE: The English Peasantry and the Enclosure of Common Fields, Gilbert Slater 1907.

[3] LEAZE: This is where it really gets complicated. Another reading of this is that it is an example of what is known as a ‘cattlegate’. These were found mainly in northern England and were in fact leasehold agreements to graze animals on a piece of land. They were made to individuals and could be passed on or sold by the leaze holder just as modern leases are today. The fact that these leazes were made to many people rather than just one favours the way that I have interpreted the entry.

[4] FINE: When an old copyhold tenant died and the new came to be ‘admitted’ to the tenancy they had to pay an admission ‘fine’ as it was known. This was not fixed in time as the rent was and reflected the value of the land at that time.

Categories: In Depth