A gentleman of my acquaintance remembers, as a child, being sent by his mother to collect firewood from the ‘common’. At the beginning of the second world war, with coal in short supply, firewood was still needed to cook the family’s food and heat the family home. Of course by then the common did not exist, it hadn’t existed for nearly a century having been extinguished by an inclosure act. But a mere act of parliament wasn’t going to put paid to the customs of centuries. According to season the common also provided the villagers with mushrooms, blackberries and nuts and the villagers did not give up their ‘rights’ readily. Luckily in time of war much allowance was made for them.

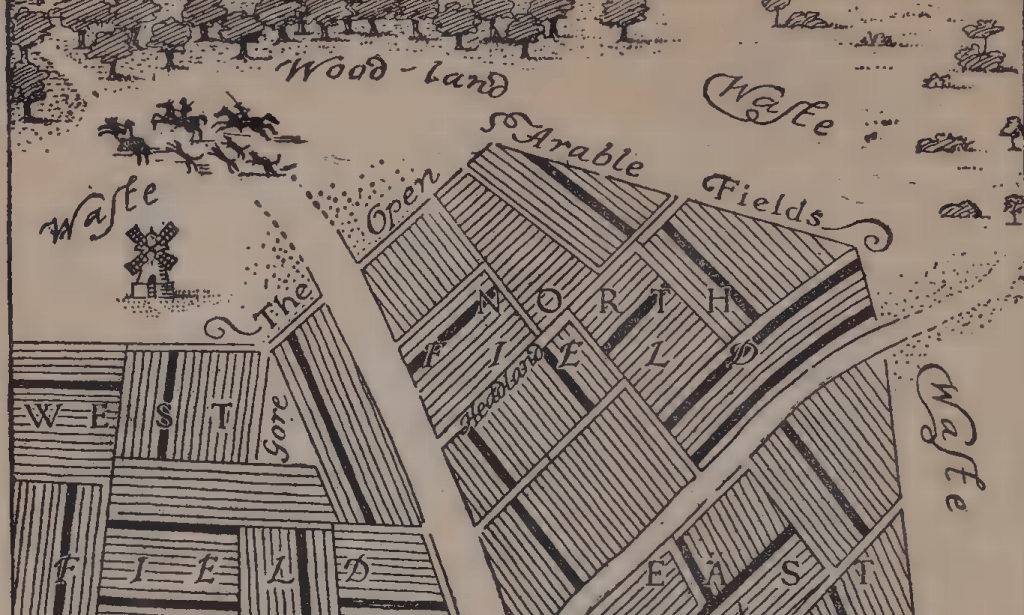

It is strange that, anciently, the most important part of the manor was given such a pejorative names as ‘the waste’. In monetary terms its value was limited but as an integral part of the open field system it was invaluable. As that system declined the crude monetary value of the land came to dominate attitudes towards it. When that occurred the waste was doomed.

Its origins were simple enough; the sparse population of the first, and early second, millennia were simply unable to cultivate large areas of the manor which, as a result, were left, by and large, as they were in their natural state. This was the waste.

Many factors affected the site of the main habitation in the manor. Proximity to the best quality of the land was perhaps the most important factor and so the waste was usually found at the periphery of the manor. As the population grew the waste formed a sort of capital reserve which could be brought into use as needed. Such encroachments, or assarts as they were known, are a common feature of the wastes of later centuries [see below] but until such time arose there was little reason to bring into cultivation land even had they the population to do so. In any case the waste had a vital role to play, far more important than mere food production, as it was the principle source of grazing within the manor, especially over winter. But although grazing was its primary function it wasn’t the only one. Natural resources such as timber, firewood, chalk, gravel, sand, turf and so on could all be extracted from the waste without disturbing good agricultural land. Of themselves these resources were only indirectly linked to agriculture but they were necessary for the survival of the inhabitants and so specific rights of common were needed to lawfully enable their extraction.

The nature of the waste could take many forms, marsh, down, heath and, a combination of woodland and pasture known, unsurprisingly as wood pasture. The quality of the land was generally poor and so was the vegetation that grew on it. It probably looked very attractive as it was home to a wide variety of plants but none of them contained much in the way of calories. This hardly mattered as there were vast tracts of the waste to compensate for its low nutritional value; as Carolina Lane pointed out, “large tracts of land were necessary to provide food for the livestock. The ratio of land to stock was high, and the [area] of land was the limiting factor in the number of livestock that could be raised”.

It followed that if the area of the waste was diminished trouble could arise. As early as 1235 [under the Statute of Merton] [1] the lord was entitled to enclose so much of the waste for his own use as he wanted so long as the free tenants had enough land left to graze their animals. No mention was made of the unfree tenants who, being in a state of near slavery, were always vulnerable to the actions of the lord.

It is difficult to say how much waste there was in the country originally as by the time of the tithe commutation large areas had already been enclosed; the full extent of the waste can only be guessed at. Occasionally however one gets a lucky break. In 1807, for example, some eight years before it was enclosed, Rampisham was surveyed by Mr Edward Watts and his map shows the position and extent of the commons there. By that time encroachments had been made on the waste but in its original form it must have comprised more than a half of the land of the manor.

The topography of the ground was important in deciding the position of the main settlement and in many parts of Dorset the waste was predominantly over the higher ground. Watts’s map, modified by me shows the effects of encroachment. This is seen at the south western end of the parish where the hachuring [as it was called] denotes slope separating the high ground from the valley below. At its full extent the waste at Rampisham was at least a third if not more of the total area of the manor.

This is seen even more clearly at Child Okeford.

The original common consisted of both the red and blue areas but by the time of the tithe commutation [1840] only the red areas survived as common land. The blue areas had previously been subject to undocumented inclosures bringing the various closes into severalty ownership. In 1845 the remaining red areas were finally inclosed but at it’s full extent the waste made up about a half of the land in the parish.

Encroachments made at the time the Statute of Merton [1235] was enacted do not seem to have caused a problem and, in the following century, the advent of the black death no doubt reduced the pressure on the waste still further. The story in the mid-16th century though was quite different. Inclosure of the arable lands was followed by them being converted to pasture for sheep. As grazing for the plough animals was no longer required, the waste too was given over to sheep, rural unemployment followed, villages were depopulated and the dispossessed roamed the countryside or moved to the towns. Very occasionally the result was open rebellion, the most famous of these being Robert Kett’s rebellion in Norfolk, made famous by C J Sansom’s last book, ‘Tombland’.

By the 18th century what had once been seen as a positive resource for the community was now vilified. The open field system and most particularly the waste was not only obstructive to agricultural improvement but a positive danger to the public good. Arthur Young [2] famously stated that “I know nothing better calculated to fill a country with barbarians ready for any mischief than extensive commons and divine service only once a month.” Youngs’ meaning was simple ; the ability of the poor to support their families by keeping a cow on the waste led to indolence, vice and a disinclination to work for their betters. When it came to inclosure, more battles were fought over the land of the waste than any other part of the manor.

[1] The Statute of Winchester 1285 extended the right.

[2] ARTHUR YOUNG: Young was a Fellow of the Royal Society and Secretary to the Board of Agriculture. All very impressive except that latter was a private organisation of like minded men and so had a particular bias towards inclosure. He himself tried farming but was not successful and pursued instead a journalistic/quasi political career.

In his later years he came to see that although inclosure had benefits the way that it was done he realised caused much harm to the poor.

Categories: In Depth