The grasslands of the manor were the second source of grass in the manor. In arable producing areas they were in relatively short supply and despite their very obvious importance to the farmers it appears that little attention was paid to them until the 16th century. The plants that lived on them were not confined to grass, one study in the 1930’s showed that there could be up to 95 different species living in ungrazed pastures although continued grazing reduced the number of varieties over time.

The grasslands were divided into those, usually called pasture, which were more or less permanently grazed and meadows, whose primary purpose was to produce hay. It is not clear how the pasture was ‘owned’. Walter of Henley, writing in the 13th century, refers to ‘the lord’s pasture’ and ‘all the other several pastures’. Walter’s comment suggests that some were exclusively owned by the lord whilst the tenants held their pastures in severalty by the free tenants. This might though be reading too much into his words.

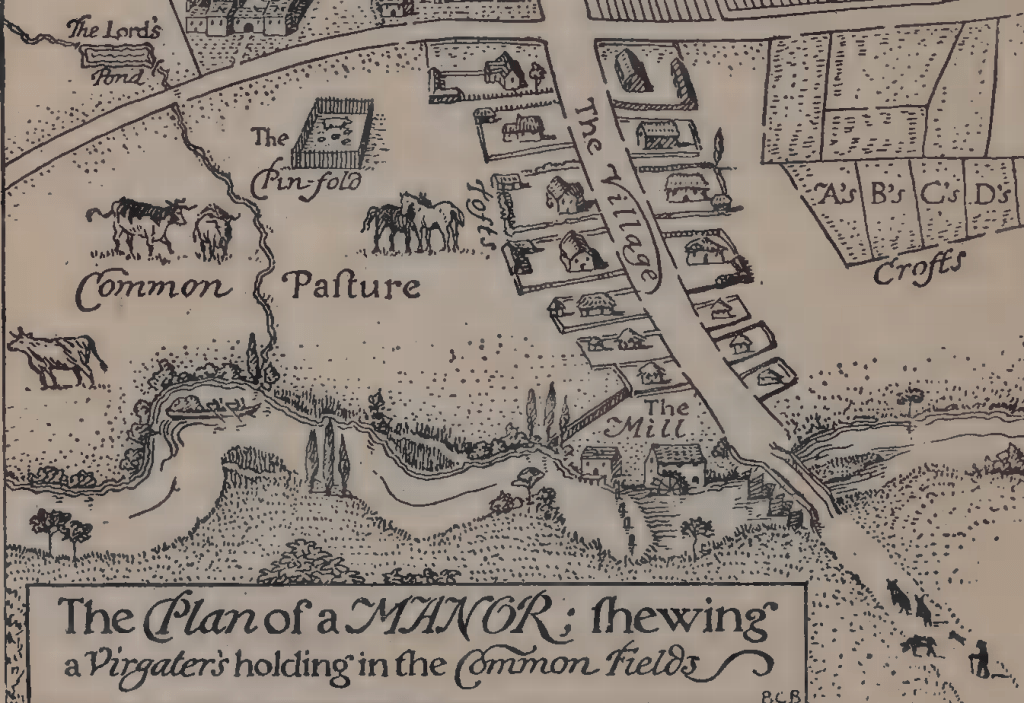

Although Hone’s map is highly stylised it has to be said that it seems to fit the pattern found in many manors. The common pasture on the left are in fact the meadow lands of the manor and for reasons described below we may assume that the plan was drawn in the autumn or early spring. As we will see, when we come to discuss the particular types of rights of common, the right to graze animals on the waste was known as the right of ‘common of pasture’ BUT the only grassland in the manor that could be subject to common of pasture were in fact the meadow lands. The pastures themselves were not commonable and as Walter of Henley suggests were held in severalty. These are shown on the right as crofts belonging to owners A, B, C etc.

Until the late 16th century the means of improving the grassland was very limited and will be the subject of a separate post. Meadow land suffered the most as regular removal of hay had a similar effect on them as removing the arable crops had on the arable fields – a reduction in their fertility. There were two ways of limiting the damage. Direct replacement of nutrients was one option albeit limited in scope. As can be seen here meadows were most often situated near rivers or streams that were prone to flooding. This deposited a thin layer of soil on them together with all their nutrients. In very cold weather, the water flowing over the meadows prevented the ground freezing and this in turn meant that when the grass began to grow again in the spring it did so more vigorously, and this offered the livestock what was referred to as an early ‘bite’. Usually the flooding was ‘natural’, but controlled flooding, in the form of ‘water meadows’, was introduced during the late 16th century.

The permanent pasture was quite often situated near the main settlement, it was simply easier to pick up and drop off the animals at either end of the working day. At Child Okeford there were a series of ‘long closes behind the town’ which served this purpose and in many villages there is a ‘behintoun lane’ which served them. These pastures had of course to be fenced [the term also implying hedges] to stop the cattle wandering and note the ‘pinfold’ where stray cattle were impounded by the pinder whose job was to round them up and then release them – for a fee.

The primary function of the meadow was to grow hay. Its use as grazing land was strictly limited and confined to a few months between the end of the hay harvest, when the hay [the foreshare] had been removed and early spring. A general pattern seems to have been that cattle were ‘depastured’ first on the ‘aftermath’ and then towards spring sheep were introduced.

Ownership of the meadow land was complicated and, although no mention is ever made of it, must originally have been linked, like common of pasturage, to the possession of arable lands. In later centuries when the pattern of agriculture had less of a bias towards arable farming we cannot be so certain as to their origin. The pastures appear to have been owned in severalty whilst the meadows enjoyed a hybrid form of ownership. The hay which grew, and thus the land that the hay grew on, was regarded as being owned in severalty for part of the year but became ‘commonable’ after the hay had been removed.

Just as the tenant held a number of strips in the arable fields so he held a number of strips in the meadow. In the arable fields each man’s strip was separated from his neighbours by a deep furrow which served the additional purpose of aiding drainage. Separating the strips in the meadow was more difficult. Furrows would have been difficult and undesirable, hedgerows would have taken up too much land and hurdles were just inconvenient in a large meadow.

Instead the meadow was retained as one large open area which instead of being divided up into real strips was divided up into what today we would call virtual strips. A good example of this can be seen at Child Okeford in 1840 when John Martin recorded the survival of this method on tithe map. It is in respect of a meadow known as Net Mead.

The meadow’s unique status is indicated by the fact that it is the only one on the map to have it’s name written in. It has a lane leading into it at top, called then as today Netmead lane, and surrounding it are a variety of closes all of which are bounded by solid lines indicating permanent hedgerows or fences. In the west it is bounded by the River Stour.

Net Mead is shown to be divided up into sixty four narrow strips which, adhering to the [surveying] conventions of the time, have been mapped by broken lines to indicate that there are no physical barriers between them. This is similar to the way that an open arable field would have been mapped but in fact Net Mead is meadow land[1].

Some indentures refer to it by an alternative name, ‘Lot’ Mead, and this gives a clue as to how the meadow was managed. As can be seen the sixty four strips vary in size and although the tithe apportionment refers to them as ‘acre’ or ‘half-acre’ the reality was that their name bore no relation to their actual measured area. These sixty four strips were owned by sixteen severalty owners and it is assumed that each was entitled to a variable number of strips depending on their common rights.

Legally then, for that year only, that particular strip was held in severalty by that owner. He had the responsibility for mowing it and carrying away his hay. It was of course unlikely that [s]he would draw the same number lot the next year and so the field was said to be held by ‘shifting severalty’.

We return to Halsbury to describe how it worked; “In many instances the severalty holding varies from year to year ….there are… the old lot meadows, in which the several portions are undivided, but are marked off by boundary stones or other marks, and the owners of the different portions draw lots for the choice each year.”

We are not entirely certain of the process as no record survives but it is assumed that, as shown on the map, the lot’s were pre-numbered and each owner drew a number out of a bag and that lot formed part of his allocation. At Child Okeford the lots were marked off with stones but in other parishes wooden ‘mead’, or ‘mear’, marks were used.

After the hay had been removed the meadow ceased temporarily to be held in severalty and instead became ‘commonable’. At this point the meadow would be opened to those with common of pasture over it. At Child Okeford the right was confined to the severalty owners. This was not always the case; in some parishes there were ‘Lammas’ lands.

Lammas lands were not found in every manor and were not confined to the meadow. Sometimes lammas lands included the open arable fields. The name comes from,‘loaf-mass’ day, an early Christian holiday, celebrated on the 1st August, when a loaf of bread was baked from the first cuttings of the harvest and brought to church for blessing. The important point about Lammas lands was that the common of pasture was not limited to the severalty owners of the land indeed Halsbury, says, “There is infinite variety in the classes of commoners over these Lammas lands as well as in the periods during which they are entitled to exercise their various rights”.

The value of good meadow land should not be underestimated as the later history of Net Mead shows as when the parish was finally inclosed in 1845 the commoners sought to retain it’s commonable status. The inclosure was undertaken by John Martin who noted the commoners were “desirous of stocking and depasturing their Allotments in the said Net Mead after the foreshare thereof hath been cut and removed and of sharing such produce as may grow thereon under proper regulations and they having made such application to me in this behalf as is in and by the said several Acts or one of them required I have determined on an attentive view and full consideration of the Premises to award order and direct all the said Allotments in the said Net Mead to be laid together and to be stocked and depastured in Common …”

The map he drew of the meadow for the inclosure award appears to be a typical post-enclosure map. The various allotments have been laid out and the solid lines appear to indicate the field has been broken up into closes each fenced off from the other. This was not the case however. There is no access to any of the allotments except by the original Net Mead lane [by Charles North’s parcel] and despite the solid lines none of the plots were actually fenced off.[2] What is interesting, and completely unexplained, is the fact that some who were allotted grass to mow were not able to graze after it had been mown whilst some of those with the right of grazing had no hay to mow.

[1] NETMEAD: The clue to the name comes from the ‘Neat’ [old English ‘beast’ or cow’ and ‘mead’ indicating meadow land.

[2] FENCED OFF: There is today one fence and a small part of the field has been turned into a small woodland.

Categories: In Depth