The subject of agricultural improvement in the 18th and 19th centuries is a vast area and is dealt with in a separate post and John Martin’s own experiments in improvement are discussed here.

In the brave new inclosed world the farmer in severalty could grow new crops, plough, sow and harvest when he chose, and breed pure strains of livestock untainted by the amorous attentions of their neighbours beasts of dubious heritage.

It was illogical therefore to replace the myriad of small un-inclosed strips in the open fields with a myriad of small strips surrounded by hedges. It was even more illogical to allow the poor commoner, with small amounts of land, or no land at all, to gain a share of the common or waste.

Then there was a moral issue. What should be done about all those who used the waste as if they were commoners yet who in law had no such right? They were little better than thieves and the ‘atmosphere of the ruling class’ denied that such people should receive compensation for loss of their ‘rights’; that would be to condone illegal activity.

These arguments were not only accepted at the time but also subsequently by some economic historians. It was not quite so simple as that however. As at Kingsclere many of these non-commoners, and their ancestors, had used the waste for many decades, seemingly with no objection; their use in many areas was regarded as a custom; a part of the common law.

Professor Duxbury [1] posed the following question ; “A law-making body might turn a custom into a law. And a community’s respect for a custom might be such that the custom operates like a law. But could a custom ever be law without it having been made so?” The medieval courts had agreed that it could. By the 18th century the jurists, derived of course from the ruling class, changed their minds and customary practices ceased to be accepted as law. The most famous example of this was the ‘Great Gleaning Case” of 1788. Gleaning, the custom of collecting leftover crops after harvesting, was widespread and thought to be a common law right. It was of considerable economic importance for the poor but a case brought before the Court of Common Pleas destroyed this idea. Even ‘prescription’, whereby an individual gained a prescriptive right to use the waste, had to be made into law by the 1832 Prescription Act as the very idea of a prescriptive right was based on a legal custom.

As E P Thompson observed; “during the eighteenth century one legal decision after another signalled that the lawyers had become converted to the notions of absolute property ownership and that (whenever the least doubt could be found) the law abhorred the messy complexities of use right”.

How many people lost out in this way can never be known. Without proof of a grant, or the support of the lord of the manor it is doubtful if their ‘claims’ ever made it beyond the in-tray of the commissioner. Even if they did, or the commoners took legal action, they would almost certainly get short shrift in the courts.

With the non-commoners out of the way all they had to concentrate on was the poorer commoner with little or no land. They were subject to a process which was dictated by monetary values pure and simple. The social value of a broad landowning class was disregarded as what was wanted was a reduction in the number of small farmers allowing the establishment of fewer larger farms. Precisely what was considered the optimal size of a farm was never made clear. Arthur Young, from his travels in East Anglia, was in favour of large farms whilst John Claridge, the Board of Agriculture reporter for Dorset in 1793 appears to have deprecated them. In any case the local topography of the county would have an impact on the average size of most farms.

It may be that the ideal farmer was the equivalent of the ‘horse farmer’ [2] described by Richard Evans who held between ten and seventy five acres of land. This size was usually farmed directly by the owner who ran the farm himself. Even Young himself accepted that some farms could be too big as they landowner would have to employ a steward, “the consequence of which is they are rarely managed so well as by the owners themselves.”

Whilst a farm of this size could be run by the owner he needed a few permanent labourers and a reservoir of temporary workers who could be called upon as required. This reservoir of labourers would come from those who now had no land or their or own or access to a common [which had of course disappeared]. It is worthwhile remembering the comment of Herefordshire farmer, John Clark: “When the commons are enclosed the labourers will work every day in the year, their children will be put out to labour early,’ and ‘that subordination of the lower ranks of society which in the present times is so much wanted, would be thereby considerably secured.’

Precisely how did inclosure produce this desirable state ? For the commoner the first hurdle to be overcome, proving a right of common, we have already considered; the second was ensuring that he or she got full recompense for the loss of their rights, which in many cases was little enough

The first step in any inclosure was to value all the lands that were to be inclosed in the parish. Then each landowner’s portion was surveyed, valued and their percentage share of the total calculated. Certain adjustments were then made to the total value. It was reduced for example by the value of the land lost to new roads, gravel pits, allotments to the poor and so on.

Some landowners did better than others. The lord of the manor’s share was increased by 20% in compensation for the loss of his ‘manorial right’, whilst the rector had his share increased for agreeing to the inclosure in the first place and in compensation in lieu of his tithe if this was to be abolished by the inclosure. He might also receive a grant of land in compensation for this as well.

Of course if their proportion of the total value went up it follows that the proportional share of all the other landowners in the parish went down.

At this stage the land surveyor practised his particular form of magic. He had to rearrange the arable fields so that each landowner received land to the proportional value of his [3] holdings.

When it came to the waste a slightly different formula was adopted. Never having been cultivated the land of the waste was, in most cases, of low value but as with the arable fields and grasslands it was surveyed and a total value obtained. That value was then divided into two.

The owner of arable lands in the manor was allotted a value of land from one half the value which was in proportion to his percentage share of the total value in the arable lands. In this case the lords 20% bonus was compensation for losing the land of the waste, which was technically owned by him although its value was always impaired because of the rights of common over it.

Next the total number of rights of common held by the commoners was counted and divided into the other half of the value of the common. Each right of common thus had a unit value and each commoner was allotted a value of land in the waste according to the number of rights of common [4] he held.

As demonstrated in a foot note the process of inclosure of itself reduced the value of the land holdings that a landowner, commoner or not, held in the manor. Only the Lord of the Manor and the Rector stood to gain and this was before the costs of the Inclosure Commissioner and Land Surveyor were taken out. Nevertheless at the end of this process the owner of arable lands in the parish was likely to have been allotted a value of land which, when translated into real acres, carved from the old open fields and the waste, was worth having.

For a commoner not in possession of arable land, whose claim might only have been based on a right of common without any land attached, the value of his claim, and thus the amount of land allotted would inevitably be small, almost certainly not enough to graze a cow or keep a pig on. Worse, and the ‘coup de grace’ for almost all of them, the costs of inclosure, the various fees paid to the commissioners, surveyors, lawyers and so on, together with their share of the road and drain costs and fencing it meant they were simply unable to take up their allotments. In some inclosures a part of the waste was sold off to pay the costs leaving no surplus to be “divided amongst the poorer sort” once the larger landowners had been paid off.

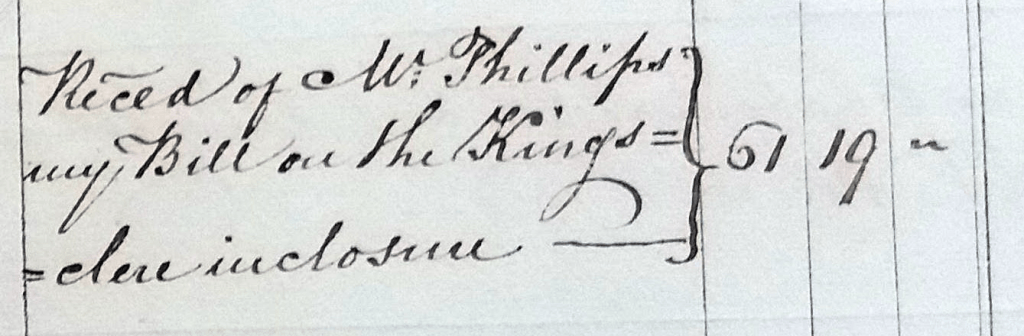

The question of value was one that exercised Mr Walter MP for Berkshire. It may be recalled that in 1845 John Martin received the payment for work that he had undertaken at Kingsclere on behalf of Mr Phillips the inclosure commissioner. Unfortunately we don’t know how much work he did but at £61 it was nearly three times the wages of a Dorset labourer.[5]

Mr Walter, opposed the inclosure in 1834 and Hansard records that “He thought that, at a moderate estimate,” the costs of the Kingsclere inclosure, “would amount to at least £5,000. And out of whose pockets was this to come? Out of the pockets of those who already enjoyed the right of commonage, without any abatement, without incurring any expense whatever. What became, he would ask, of the sum so abstracted from individuals actually enjoying a free right? Did it go to improve the land? No: it went into the pockets of commissioners, surveyors, lawyers, and persons of that class, by whom absolute havoc was to be committed upon this property.”

Here is the nub of the problem. The commoners were being asked to give up a right they enjoyed without any ‘abatement’ or ‘expense’? No rational commoner would have accepted that deal, given the expenses of inclosure. Fortunately the law, in the form of a parliamentary act, came to the rescue of the ruling classes and at the end of the day it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that it was because the ruling class “needlessly sacrificed” the poor as the Hammonds claimed.

Could it have been different? The answer has to be yes. Arthur Young, that arch-incloser, demonstrated that it could have been. It was not because of ignorance or lack of evidence that the poor were sacrificed. Young provided good economic evidence of the benefits of the poor having access to land. He showed that the provision of a cottage and three acres would cost some £50 per year and support a family of five whilst that same family, confined to the workhouse, would cost the parish £60! Furthermore some land owners had provided cow-pastures, land carved from the waste, inclosed and then rented to the poor, with good effect on the poor rate. Even small amounts of land had a beneficial effect and some landowners such as the Duke of Bedford, Earl of Egremont and Lord Hardwicke provided cottage gardens and offered prizes for the best produce.

The trouble was, as Young, found these were in the minority. In 25 out of 37 recent inclosures [circa 1800] he found no provision for the poor had been made and that their condition had deteriorated. As the Hammonds made clear, “these proposals were disregarded, not necessarily from wickedness or rapacity, but because the atmosphere of the ruling class was unfavourable”.

They did so perhaps not because of wickedness but can they be excused rapacity? That’s another matter because, despite the Hammonds claims that it was not due to rapacity, they provided ample evidence that on many occasions the inclosure proceeded as it did because of greed. There was nothing in the way that inclosures were conducted that could not have been changed. The inclosure commissioner with the agreement of the landowners was pretty much free to conduct the inclosure as they wanted. Had they chosen to do they could have acknowledged the claims of the non-commoners, they could have taken a broader view of what constituted ‘the value of the thing’, they could in short have been more generous. But to do so would have seen their own potential gains fall and this they were not prepared to do.

[1] DUXBURY: Duxbury, Neil (2017) Custom as law in English law. Cambridge Law Journal.

[2] COW FARMER: Richard Evans in his book “The Third Reich in Power” describes agriculture in a small village in Germany. I suspect the average late 18th and early 19th century village in England was little different.

“In the Hessian village of Korle, for instance with roughly a thousand souls around 1930, the community was split into three main groups. At the top were ‘horse farmers’, fourteen substantial peasant farmers with between ten and thirty hectares each, producing enough of a surplus for the market to be able to keep horses and employ labourers and maids on a permanent basis and more temporarily at harvest time. In the middle were the ‘cow-farmers’, sixty six of them in 1928, who were more or less self sufficient with 2 to 10 hectares [5 – 25 acres] of land apiece but depended for labour on their own relatives and occasionally employed extra labourers at time of need, though they generally paid them in kind rather than in money. Finally, at the bottom of the social heap there were the ‘goat-farmers’, eighty households with less than two hectares each, dependent on the loan of draught animals and ploughs from the horse farmers and paying for their services by working for them at times in return”.

[3] PROPORTIONAL VALUE: Suppose the original value of the land to be inclosed was £100 and that the value of your land before inclosure was £10. You would own 10% of the total value.

Now suppose that after compensating the lord of the manor and rector, your percentage share of this total has fallen to 8% and that the new ‘total value’, after allowing for the value of the land removed for new roads etc, has fallen to £90, your allotment will be £7.

[4] RIGHTS OF COMMON: Interestingly Stephenson in his “THE SYSTEM of LAND SURVEYING AT PRESENT ADOPTED BY SURVEYORS AND COMMISSIONERS IN OLD AND NEW INCLOSURES” published in 1805 allows the lord of the manor a number of rights of common. Strictly speaking he could not be a commoner in his own manor but he did of course have the right to graze cattle on his own waste and Stephenson ‘translated’ the number of cattle into the equivalent number of rights of common.

[5] DORSET LABOURER: Admittedly the poorest paid in the country at 8s per week in the winter. They may have been slightly higher by a shilling or so in Wiltshire. Source: ‘Regional Agricultural wage Variations in early 19th Century England’ . M Lyle BAHR Vol 55 2007

Categories: In Depth