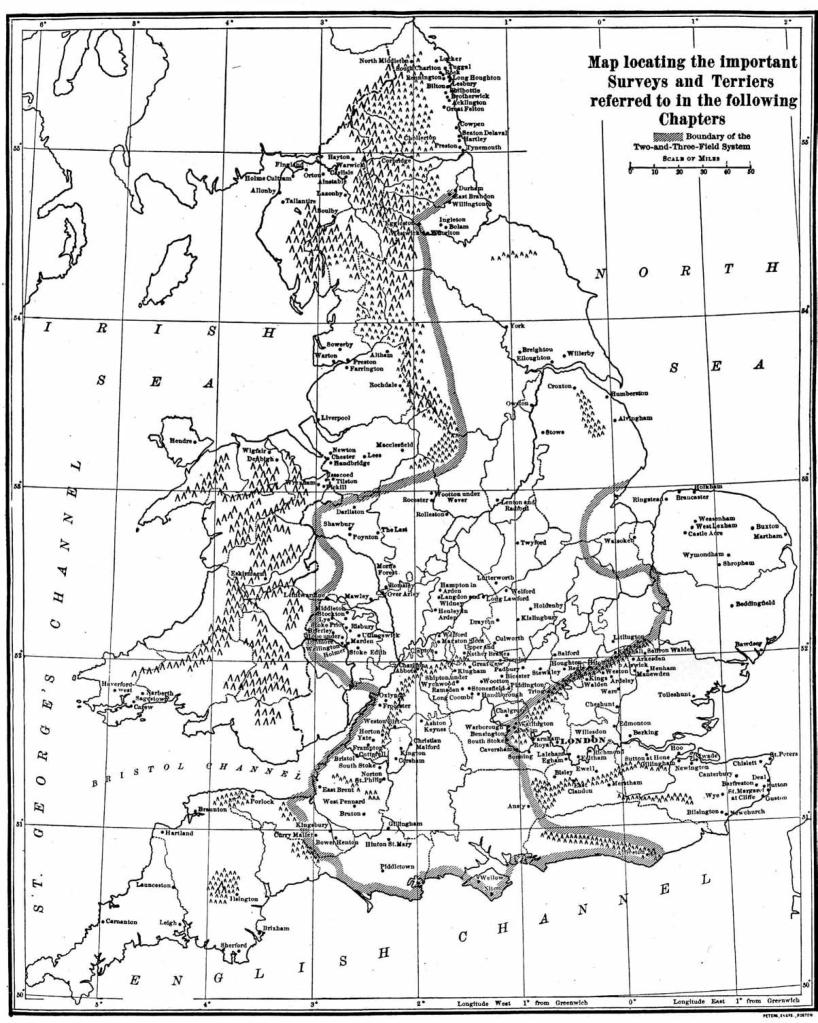

Draw a line from Durham in the north, to Devon in the west, and from the Wash in the East, to Sussex in the south and you have a swathe of the country which at one time was almost exclusively given over to what was called the common, or open field system. Based around the ‘Manor’ it was probably introduced by the Anglo-Saxon’s but the form described below was really a product of the early Norman kings and the feudal system. In theory, under the feudal system, only the king could own land , everyone else was a tenant who ‘held’ the land. I use the terms hold/own interchangeably as also with manor/parish. Manor’s were invented before parishes but in time manor’s decayed but parishes survived.

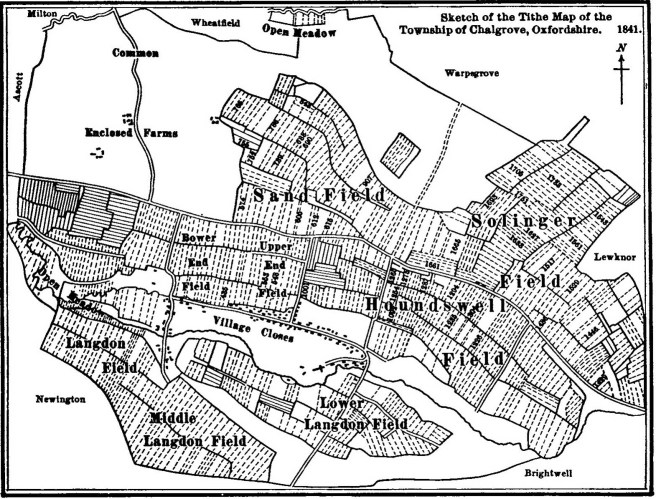

Had it been possible to view an open field parish from the air, in, let us say the 12th century, you would have seen [typically] three large arable fields of several hundred acres each. In practice as the sketch below shows there were often many more. They were rarely entirely open, cereal crops are a magnet for livestock so that most fields were probably hedged at their outer boundaries but internally there were no fences or hedges to break the field up. In most parishes at the geographic centre of the fields was the cluster of buildings that comprised the village- when you have to walk to work, you don’t want it to be too far away from your home. When you return your livestock at night it is best to fold them where an eye can be kept on them.

The drawing above shows the open fields of Chalgrove in Oxfordshire. The common arable fields are filled with hundreds of hatched strips [ = = =] but in large parishes their could be quite literally thousands of these strips. The strips are seperated from each other by solid lines which are baulks [balks] which allow access to the strips from the green lanes that comprise the roads of the village. The strips were often grouped together into what were called furlongs and were orientated in a way that allowed for easy ploughing or drainage.

Nominally the strips were of a size that was said to represent the area that a single plough team could plough in one day. Equally nominally they were said to be 220 yards by 22 yards which is an area equivalent to the statute acre. If ploughed using a particular technique the strips gradually assumed a convex shape, a central ridge falling away to a furrow on either side, giving rise to a distinctive appearance which can still be seen today where ploughing has not destroyed them.

This ridge and furrow appearance is clear evidence of an open field system but it’s absence does not indicated some other system of farming. The shape is determined by the need for drainage and in areas where this was not required another technique of ploughing was used which still resulted in furrows and a small ridge, but not the convex shape. At ground level it would be seen that roughly a third of the fields were were growing wheat, another third barley or oats and the remainder was left fallow. It had been found that continual cropping of the fields reduced their fertility but by allowing it allow fallow one year in three the fertility was maintained. Each year the cropping of the fields was rotated and in later centuries the fallow was planted up with crops such as clover or lucerne which further replenished the soil and could be harvested as animal fodder or used as pasture for them.

An individual farmer would hold a number of strips, the number varying with his status, and because one field was always fallow the strips were distributed across all the fields. In the earliest centuries at least the strips were rarely next to each other in order that each person would have a mixture of soil qualities.

The most valuable land in any parish were the grasslands comprising meadow and pasture. The open field system was wholly dependent on the oxen [later horses] which ploughed the arable lands. If they died then so would the villagers, for it was simply not possible to plough the land without them. In Chalgrove, near the village houses, were the “Village Closes”. This was pasture that was enclosed by hedges and where the livestock would be returned to at night, having spent the day in the open meadow or on the common, or, as it was then known, the waste. In the earliest centuries grasslands were in short supply but in many areas of the country the grasslands would gradually reduce the area given over to arable crops.

The meadow land was assiduously protected. It had the primary purpose of growing hay and was only grazed for limited periods during the year. A commoner with rights in the ‘common pasture’, [see below], would be in possession of strips of grassland. These were delineated by a variety of wooden ‘mead’ marks or marker stones and each commoner would be responsible, at the time of the hay harvest, for mowing his own hay and carrying it away. This hay was what saw the oxen through the winter. Before the days of artificial feeds to lose a hay rick to wind or fire was an unimaginable disaster that could lead to starvation for the human population then next year. After the hay harvest the meadow would be used for grazing and, since it was difficult to keep cattle confined to thin strips, this necessarily meant that all the commoners animals grazed together. In later centuries, to prevent overstocking, the grazing was ‘stinted’ so that only a certain number of animals could be grazed on the meadows. In any case during the late autumn the animals were taken off and the grass was allowed to grow untouched until the next hay harvest.

Had it been possible to see the boundaries of the manor or parish it would have been observed that the majority of the parish was in fact occupied by a large area of land that did not fit this neat pattern; it looked as if it was uncultivated, which it was, and uninhabited which quite often it wasn’t. This was the ‘waste’ of the parish; in time it would become known as the common but as this word has a multiplicity of meaning I prefer to use the term waste. In a period when the population was sparse and the land area large, it was simply not possible to cultivate all the land of the manor and the residue, usually the poorer quality or more distant part of the parish was left uncultivated. The waste belonged to the Lord of the Manor and was what we might call ‘reserve land’ which could be brought into cultivation if necessary.

COMMONERS, RIGHTS OF COMMON AND CUSTOMS.

The physical structure of the open fields was in some senses the least part of the open field system ; what made it work was a complex set of legal and social relationships between the inhabitants of the village. The manor was no democracy but at all levels in society there was some acknowledgment of the interdependence of the inhabitants. Unseen, yet enveloping everything in the parish or manor, were a set of practices which ensured the survival of all. Firstly there were the orders of the manorial court which regulated the course of agriculture in the manor and secondly the customs of the manor which in some measure protected the villagers from any arbitrary actions of the lord. In time these would gain the protection of the common law and some would become common rights. This is a highly complex area and it must be stressed that what follows is a greatly simplified account.

To possess a ‘right of common’, allowed, in simple terms, one man to make a profit from the land of another. The land itself remained with it’s original owner and the man or woman who owned a right of common was known as a commoner. In general there were three types of common rights and two ways of becoming a commoner.

RIGHTS OF COMMON

- Rights in the open arable fields. There was never a right of common to possess land in the open fields. In an era when, if you wanted to eat, most people had to grow it for themselves, possession of land was a necessity but it managed by a complex tenures system that allowed people to hold land in exchange for a series of feudal services. The only exceptions were the lord himself [who got others to grow it for him] and slaves whose sustenance came directly from the lord. Possession of some land in the open arable fields was thus a necessity and all other rights of common stemmed from this right. Although there was no right to be granted land there was frequently a right of common to grazing on the stubble after the corn harvest.

- Rights in the common pasture – the grasslands of the parish.

- Rights in the waste of the manor. The land of the waste belonged , legally, to the lord of the manor but from the earliest centuries the villagers had the right to use it to provide for their needs. Indeed they had no choice. The earliest right , known as common appendant, arose from the need to feed the oxen or horses over the winter season. Sir William Blackstone takes up the story; “Common appendant is a right, belonging to the owners or occupiers of arable land, to put commonable beasts upon the lord’s waste, and upon the land of other persons within the same manor. Commonable beasts are either beasts of the plow, or such as manure the ground. This is a matter of most universal right; and it was originally permitted, not only for the encouragement of agriculture, but for the necessity of the thing. For, when lords of manors granted out parcels of land to tenants, for services either done or to be done, these tenants could not plow or manure the land without beasts; these beasts could not be sustained without pasture; and pasture could not be had but in the lord’s wastes, and on the unenclosed fallow grounds”. The grass that was eaten by these animals would in other circumstances have been eaten by the Lord’s animals. However when the commoner’s animals ate it the commoner was technically taking a profit from the land.

Appendant rights could never be detached from the land, except by way of an act of parliament. Even when a particular portion of land had been divided into smaller parts, each new part had a share of the whole right. Appendant rights were limited to animals ‘Levant and Couchant’. This literally means ‘rising up and laying down’ but in the context of appendant rights it means that only animals which could be maintained throughout the winter on the land to which the right was appendant could be grazed on the waste. In effect this meant restricting the stock to sheep, horses and cattle.

The waste supplied many of the other needs of the villagers and by the end of the 13th century these needs had to be addressed . After the year 1290 AD a new form of common right came into being known as common appurtenant. This produced a much wider range of rights and extended to a larger number of people who could claim them. It allowed animals, other than cattle and sheep, to be grazed on the common and extended the range of rights to, for example taking wood,sand, turf or furze from the waste. There was an important change however for these new rights were by ‘prescription’, which is to say they were rights that were dependent on a specific grant made by the lord of the manor. This grant though was not to a particular individual but was attached to particular parcels of land.

Rights of common were so diverse that only a general outline can be given. They were universal, in that such rights were to be found in all open field parishes and, when correctly granted, were protected under the common law. The most frequent right was common of pasture. This allowed the depasturing of cattle, horses or sheep on the waste as well as the common meadow fields after the hay harvest. Indeed they could be extended to grazing over any piece of greensward as it was known including the verges of the roads and the balks that separated the arable strips. There were many other rights though, a commoner might have the right to take firewood, turf, furze, chalk, gravel and so on for their own use. Their exact nature though varied from manor to manor ; a commoner in manor A might, for example, be able to take chalk but in the next door manor there might be no such right.

BECOMING A COMMONER

By the 18th and 19th centuries the number of commoners had fallen and in many places the number of villagers without common rights exceeded those who had them. We may imagine that in medieval times the vast majority of villagers were commoners but over the centuries, as the population grew and as manors decayed their numbers declined. Neeson [Commoners : Common Right, Enclosure and Social Change in England, 1993] found two large groups of commoners.

- Rights attached to land. Possession of land was the commonest way of obtaining a right of common. Where the right was appendent it might be reduced ‘pro rata’ if part of the land had been sold but where it was appurtenant local custom determined whether or not the right could be used. For example in some manors the commoner had to own 10 acres before the right could be exercised whereas in others it was as low as an acre.

- Cottagers. Anciently there existed an entity known as a ‘messuage’. This was a cottage , or farm buildings to which specific parcels of land were annexed and to which rights of common were also attached. In time these rights could become detached from the land and applied to the cottage itself but just to show how complex these rights could be Neeson also found examples where the cottager had bequeathed his cottage to one child and the right of common to another child who lived outside the manor.

The following example of common rights comes from Child Okeford in 1826. It is part of a manorial survey or terrier listing the commoners owing homage to the lord of the manor of Child Okeford Superior.

The first thing to note is that the tenant was the widow of Henry Jenkins. The tenancy was a copyhold tenancy and it was the custom of the parish to allow widows ‘free bench’ – the ability to inherit the tenancy on the death of the husband. We do not know her first name but she was a commoner by virtue of the fact she was in possession of a cottage and land to which common rights were attached.

The rights to which she was entitled were fairly standard. Net Mead was the common meadow of the parish. a large field of some thirty acres, completely open but divided up into ‘virtual strips’ belonging to various owners and marked out by mark stones. Widow Jenkins had the right to take the hay from 3 acres of the land.

At the same time she was allowed to graze 1 horse, 2 cows and 10 sheeps on the main common in the parish [Okeford Common] whereas in an outyling part of the parish [Gobson Common] she was allowed to graze two cows.

The final right though defies explanation. Most commoners not only had the right to take the hay from the meadow [the foreshare] but were, for a short time afterwards allowed to graze their animals on the meadow. Twin acre was a small meadow which numerous villagers who were not commoners were entitled to use but on a very sporadic basis as was the case with Widow Jenkins who could only claim the hay twice in twelve years. She was not however allowed to graze her cows after the harvest, that right belonging to another tenant of the manor. How such rights arose can never be known.

Grazing rights in the parish were expressed in terms of ‘leazes’ with the number of animals grazed being determined by the number of leazes. Some rights in the same parish allowed grazing for two cows a year but three every third year. Even more strangely some owners had [for example] 10 1/2 leazes. Since you cannot graze a half a cow the explanation is that the leaze lasted for six months and not a full year. Child Okeford common was a stinted common which is to say that although the right to graze cattle on it was a common right the number of animals that could be grazed could be varied each year to avoid destruction of the common through over grazing.

The Rest !

To this rather restricted group of commoners we must add a third and much larger group of villagers who had no legal rights over the common fields, the waste, or pasture. There is no collective name for this group, whom we might just as well term non-commoners. It is not at all clear how rights of common came to be lost. In the manor with which I am most familiar, Child Okeford, there was a significant reduction in the number of customary tenants between 1653 [when the incomplete records record eleven] and 1845 when the inclosure award acknowledged just one. Since the customary tenants were highly likely to have rights of common their loss would have reduced the number of commoners. In 1839 when the tithe was commuted the Instrument of Apportionment shows that there were many non-commoners who had quite substantial holdings but these men and women were not the problem. It was the poor who would cause most problems for the inclosure commissioners, particularly when it came to the waste.

Non-commoners had the same needs as the commoners. Their need for firewood was just as great as the commoners and many owned or shared in the ownership of a pig which could be fattened on the mast [beech or oak nuts] found on many commons. If they were lucky they may even have had a cow that needed grazing. The waste provided them with nuts and berries and it would never have occurred to them that such items, the bounty of nature, were actually the property of the lord of the manor. Few were versed in property law but most had a keen sense of justice and believed they had the right to use the waste. It is doubtful that they would have understood the legal nicety that allowed their neighbour to gather firewood but which barred them.

As a consequence many came to believe that they had accrued rights in the waste simply because their customs had been practiced for so long. Such a belief was not unreasonable. Local customs covered virtually every activity in the parish. Tenures, tithes, poor law assessment, by-laws, heriots and religious oblations were all customary in nature. Frequently these pseudo-rights were of great duration and had been tolerated by the lords and commoners for pragmatic reasons -villagers with a means of supporting themselves were less likely to claim poor relief. In the 18th century this pragmatism disappeared.

When it came to inclose the lands of the manor or parish the commissioner had then to consider two types of right. Those which had a firm legal basis, but which were rare, and a ‘right’ that existed in the collective memory of the villagers but which could not be proven at law. The inclosure commissioners had little choice but to acknowledge the former, but in 1788 an important legal ruling enabled them to ignore the latter.

For centuries women and children had gone gleaning. Harvesting using the scythe resulted in stooks of wheat or barley where the head was attached to the stalk. Inevitably though some heads became detached and fell to the ground and when the harvest was completed the women and children of the village would collect these for the use of the family. Although it was not a common right , gleaning was believed to be a custom that was protected under common law. As they were to discover they weren’t. In a case brought before the Court of Common Pleas in 1788 it was decided that customs such as this were not in fact protected by common law.

The decision was not entirely unbiased. Lord Loughborough the chief justice who heard the case was an active proponent of inclosure and regarded gleaning as “destructive of the peace and good order of society.” Various legal reasons were produced against gleaning , but the argument that gleaned crops reduced the farmer’s profits and thus reduced his ability to pay his poor rates with which the poor were paid, must be one of the most irrational ever produced by a judge. The obvious counter argument, that allowing the poor to retain the gleaned crop meant that fewer of them would need poor relief in the first place, seems not to have occured to him.

The case was important because it served as a precedent whenever a question of customary practice appeared in the courts and it’s implications were immediately obvious to those who favoured inclosure. If the customary practices of the villagers had no basis in law then any claim for a right of common that could not be proven could be disregarded.

The distinction between ‘legal’ rights of common and the non-legal has led some historians to argue that the poor did not suffer when inclosure took place. After all you could not really complain if you were deprived of something that you were not entitled to in the first place but this ignores the essence of the open field system as it was originally conceived. The society that gave rise to the system was never an equal one ,it was never some kind of socialist commune but for all that it was a communal system. It was one where the needs of the community had at least to be considered and where the strict legal rights of individual were not allowed to ruin the well being of the community as a whole.

FUNCTION

I have already looked at the function of the Manorial Court’s in respect of the manor of Rampisham but this gives a pale indication of the way that a fully open manor would have worked. By John Martin’s time most open parishes in Dorset had enclosed their arable lands, in most manors only the waste remained to be inclosed and the rules regulating them were considerably less complex.The manor was not some kind of communist or socialist idyll, for each man was responsible for tending his own strips and producing food for himself and his family and it was not uncommon for one man to try and better himself at the expense of others. Ploughing, broadcasting , weeding, bird scaring, harvesting and gleaning were all communal activities which had to be coordinated because for better or worse the manor was a community of individuals who were mutually dependent on one another and had, perforce to work together. The means of regulating the commons and the commoners was the Court Baron. For the way in which an open field manor operated the reader can do no better than C. S. & C.S. Orwin’s accounts of the open field system at Laxton published in 1938. Laxton was and still is the last remaining open field parish in England.

Next : Why Inclose?

Latest Posts: