Land is the source of all material wealth. From it we get everything that we use or value, whether it be food, clothing, fuel, shelter, metal, or precious stones. We live on the land and from the land, and to the land our bodies or our ashes are committed when we die. The availability of land is the key to human existence, and its distribution and use are of vital importance. [Land Law and Registration S Rowton Simpson 1976]

It is doubtful if many people who own their own house today realise that technically they are ‘tenants in fee simple’ and that theoretically even today the land and house could revert one day to the Crown. How did this arise ?

Property real and otherwise.

What makes an item or object someone’s ‘property’? It’s a question that has intrigued philosophers over the generations and not easy to answer for there is nothing that inheres in any object that says “I am property”. Close examination reveals that in fact anything can, and has, been regarded as property so long as there is a body of law encompassing it and a means of enforcing that law. As Stanford University’s Encylopedia of Philosophy puts it “ ‘property’ is a general term for the rules that govern people’s access to and control of things like land, natural resources, the means of production, manufactured goods, and also (on some accounts) texts, ideas, inventions, and other intellectual products.”

Land , has two characteristics which most other forms of property do not have. It cannot be legally destroyed [any parcel of land is deemed to extend down to the centre of the earth and up into outer space] and it is of course immovable. Both these attributes mean that land is useful in ways that other forms of property are not; in particular it allows the current owner to plan for the future. Fortunes might be squandered, jewels can be lost, sold or stolen, but land is fixed , immutable and less readily disposed of. Anciently it’s main value was that it could be demised [left] to a person’s heirs with, if necessary restrictions applied to it’s future use.

As a form of property then land has unique properties and with the development of common law in the medieval period it was regarded differently to ‘Personal’ property, such as money, goods or other moveable items. Malefactors might steal or destroy such objects but the law agreed that [if the thief had been caught] a monetary payment of equal value would be adequate restitution for the owner’s loss. Land though was different , a differentiation that was reflected in the fact that it was known as ‘Realty’ or ‘real’ property. The word ‘real’ derives from the Latin ‘res’ or ‘thing’ and as land was immovable the law considered that the only remedy for an owner wrongly deprived of his land was the restoration of the ‘thing’, which is to say the land. The distinction between the types of property survives to this day in the term ‘real estate’.

Feudalism

Rarely is the beginning of a story it’s actual beginning ; but we have to start somewhere and Europe after the Norman Conquest of England is a good time to start. It was a turbulent world but there were the first glimmerings of a more stable and settled future; the result of a new hierarchical system in society. In the seventeenth century, according to Asa Briggs, a social historian, this came to be called the feudal system and the era in which it took place – the medieval. With a King at the top, the peasantry at the bottom and a whole host of middle men in between, stability was achieved by each level in society owing some form of duty or service to the level above. Every man had to have a master and in 1531 a statute decreed,

” if any man or woman being whole and mighty in body and able to labour having no land, master, nor using any lawful merchandise ..be vagrant” then they were to be brought to the Justices of the Peace in the local market town and ” there to be tied to the end of a cart naked and be beaten by whips throughout the same market town or other place till his body be bloody by reason of such whipping.”

Tough times.

At all levels of society, individuals attended ceremonies at which subordinates offered oaths to their over lord. Oaths of fealty meant little more than that the oath taker would be truthful but oaths of homage were much more important. An oath of homage was an acknowledgement that the oath taker owed his overlord some form of service in exchange for the lands the lord granted him.

The King having no overlord , other than God, it was assumed [and accepted by the rest of society] that he alone was the only person who could actually own land – in technical terms he was known as the ‘allodial owner’ of all of England’s land. The consequences of this were that no ordinary citizen owned land in the way that we understand the word ‘own’ today. Nor, initially, could they buy, sell or bequeath it to any heirs or successors. The word ‘tenere’ in latin means to hold and it gives rise to some of our modern words

- Tenant – the individual or organisation who holds the land in question

- Tenure- the terms and conditions on which the land was held

- Tenement – the lands that were held.

William’s initial grants of land were made to his ‘tenants- in – chief’ as they would become known. According to the number of the estates they were granted these tenants-in-chief were able to grant land to their own tenants, who became known as ‘mesne’ or intermediate lords a process known as sub-infeudation. The result being a cascade of tenancies of various sizes. At the bottom was the fundamental unit of feudal life – the manor. Since none of these people owned their lands, in theory at least, on the death of the tenant the land should have gone back [escheated] to the King. This was clearly not a great incentive for those who wanted their children to inherit the land and so built into the feudal system was a mechanism by which this could be done.

Feudal Incidents

Tenants not only had to provide some service to their overlord [dealt with below] but also had to agree to the payment of what were known as feudal incidents. These were wide ranging in extent but the most important were known as ‘feudal relief’ and ‘premier seisin’. If a tenant died the land was ‘surrendered’ to the overlord who, if the tenant’s heir paid a ‘relief’, then admitted the heir as the new tenant. Once the relief was paid the heir continued to occupy the land uninterrupted, so long as he performed his feudal service. Once [s]he died the process was repeated with the new heir. This system had flaws. The process of surrender and admission always introduced breaks into the chain of inheritance. In an age when the common law was barely developed there was a customary right of inheritance but it was not automatic. The overlord , for example, was entitled to income from their ex- tenants lands until the heir had paid the relief . This right, known as ‘premier seisin’, gave little incentive for the overlord to claim their relief immediately and led many to setting extortionate rates of relief which took a long time for the heir to raise. King John was the worst abuser of this right and it was one of the direct causes of his barons rebelling and him being forced to sign Magna Carta in 1215.

“If any earl, baron, or other person that holds lands directly of the Crown, for military service, shall die, and at his death his heir shall be of full age and owe a ‘relief’, the heir shall have his inheritance on payment of the ancient scale of ‘relief’. That is to say, the heir or heirs of an earl shall pay £100 for the entire earl’s barony, the heir or heirs of a knight 100s. at most for the entire knight’s ‘fee’, and any man that owes less shall pay less, in accordance with the ancient usage of ‘fees’.”

Although the Magna Carta was aimed at the King a similar principle operated lower down the social scale and by the 13th century the right to claim premier seisin by the tenants in chief was abolished. In future only the King could claim premier seisin and in 1660 all remaining feudal incidents were abolished from freehold land [see below].

The ideas behind feudal relief persisted well into the future however. Our modern form of inheritance tax has it’s origins in such ideas. More importantly for the future though was the development of a form of tenure that allowed land to be passed down the generations with no limit to the length of time on the tenure. As long as an heir had been nominated and the relief had been paid the tenancy continued within a line of succession. Only if no heir, or possible heir, existed would the land return to the crown.

Feudal Service

Feudal incidents were not the only payments made to the King or overlord. In exchange for the land the tenant had to provide some form of service. The most prestigious and honourable form of tenure was ‘Free’ service and the most servile was known, as you might guess, as unfree service.

Free Service

We will start with Free service of which there were several forms such as serjeanty [non military service to the king] and frankalmoign [praying] but these are not considered here. The most important ‘free’ service was to provide military help to the King or overlord when called upon to do so. As the centuries passed the nature of free services changed and some forms of agricultural service became recognised as being ‘free’. In contrast to the unfree tenant the free holder, or freeman as he was known, the amount of work they had to perform was defined and limited.

Unsurprisingly land held by free service became known as freehold land and as the centuries passed all forms of free service disappeared to be replaced by a simple monetary payment known as a ‘quit rent’ ; paid quite literally to be quit of his feudal service. As the value of money declined with time quit rents became too expensive to collect and were abandoned. The same thing applied to feudal incidents; Magna Carta was just the beginning of the end and as far as they were concerned as the common law developed they became more tightly regulated and appear in many cases to have been abandoned until finally, in 1660, the Tenures abolition act abolished almost all feudal incidents granting the king [Charles II] a tax on alcohol to replace his lost income .

The result of all this was that although freeholders were still technically tenants the process of surrender and admission ceased and inheritance of the land became potentially perpetual without a break.

The Statute of Quia Emptores 1290

In 1290 the feudal system suffered what was to be a fatal blow. The original intention of William the Conqueror had been that all grants of land should be life tenures and would revert to the crown on the tenant’s death and would then be reallocated. This was clearly not going to satisfy the Barons and by 1100 land was being inherited on payment to the King or overlord of a feudal relief.

The process of sub-infeudation however led to so many complications in the apportionment of the service that it was effectively abolished by the statute of Quia emptores. “A free tenant was henceforth forbidden to sub-infeudate but was permitted to alienate the whole or part of his land by substitution, that is, the new tenant took the place of the former tenant, who departed from the scene.” [Simpson ibid] In this way the chain of tenancies, incidents and service was broken leading to the modern concept of freehold as one of absolute ownership. It now remains to consider what happened to the land under unfree tenure.

Unfree or villein tenure, later called copyhold.

In an era when, if you wanted to eat, you had to grow your own food everyone had to hold some land on which to grow it. For nearly three hundred years after the Norman Conquest the people at the bottom of the social pile held their small portion of land in ‘villeinage’, as unfree or servile tenure was named. Slavery would be another.

Most unfree service involved working on the Lord’s land but unlike free service, where the number of days was limited, the services these people had to provide varied entirely with the whim of the lord of the manor. If they had to work for him seven days a week so be it. In the 14th century the ravages of the Black Death gave the survivors a slight upper hand. After this time the manorial lord could no longer behave arbitrarily but had to conform to the custom of the manor. This was a small but important concession and was enforceable under common law ; it is the origin of many later common rights.

At some time or other it was recognised that it was to the advantage of the Lord and the unfree tenants, that the villeins should be allowed to pass the land they held on to their heirs. Tenure in villeinage was gradually replaced by ‘tenure by copy of the court roll’ or ‘copyhold’ so called because it was recorded in the court roll of the manor.

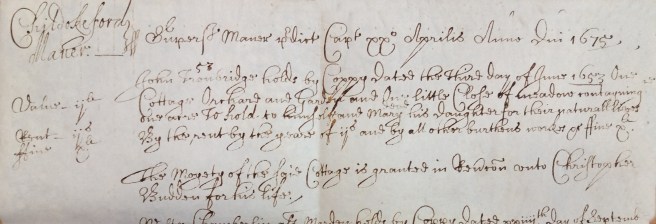

The example below is taken from the Court roll of Child Okeford.

“Child Okeford Maner #### of Manor Court 22nd April Year of Our Lord 1675

John Trowbridge holds by Coppy Dated the third day of June 1653 one Cottage One house and Garden and one little close of meadow containing one acre To hold to himself and Mary his daughter for their natural lives By the paym[en]t by the year of 6s [4] and by All other burthens works and Ffines

The Moiety of the joint cottage is granted in #### unto Christopher Budden for five lifes”

The precise date at which copyhold tenures came into existence is not known. The great jurist, Sir Edward Coke writing in the 17th century noted that ‘tenants by copy is but a new-found name, for in

ancient times they were called tenants in villeinage’. Writing in the 21st century researcher Mark Bailey wrote “Although much is known about villein tenure in c.1300, and about copyholds from c.1550,

less is known about the transformation from one to the other.”

To generalise about copyhold tenancies is difficult because there was, as another author, noted, “a bewildering variety” of local forms. There were two main versions however. which differed in their geographical extent.

In ‘the North’, Midlands, East Anglia and the Home Counties the commonest form was known as ‘Copyhold of Inheritance‘. This type was the most generous of the two forms as it was tantamount to holding a freehold estate, albeit with some stipulations. These copyholds could be bought or sold by the tenant without the permission of the lord of the manor BUT, and it was an important BUT, they were still legally tenants of the manor. They had to attend the manorial court, which still had to record changes in ownership, and they also had to pay their customary dues [see below].

The second form was found in the south of England, the West Country and parts of Hampshire and Oxfordshire and was known as ‘Copyhold for lives’. The tenure was granted for a number of lives, typically three, who were named on the tenancy and as each person died another could be added by a process of surrender and admittance [see here for an example at Rampisham]. The surrender of a tenancy was usually brought about by the death of the tenant following which the next life on the tenancy would be admitted to the tenancy on payment of the heriot. The addition of a new life to the tenancy was at the tenants request and in general could not be blocked by the lord of the manor, so long as it accorded with the custom of the manor; such a right was protected at common law.

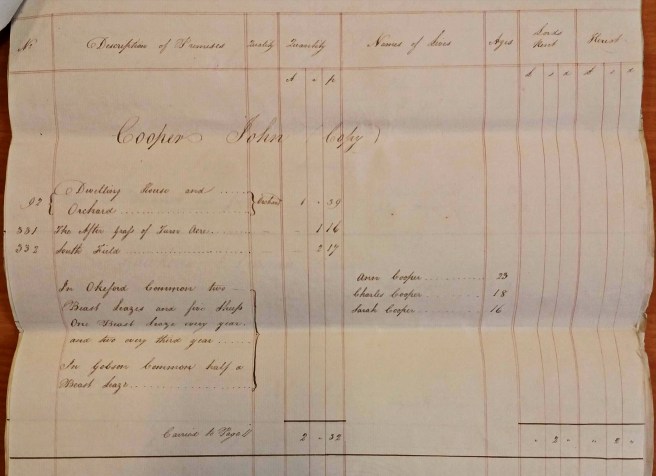

An example of a copyhold for lives, again from Child Okeford, is shown below.

Dating from 1826 we can see the essential components of the tenancy. We don’t know much about John Cooper but might assume that he was an older man as the three lives named on the copy are his children. Wives were not always named on the tenancy as they were said to have a ‘free bench’ meaning they could occupy the house and land after their husbands’ death. He was in possession of a house and orchard together with a little over a half acre of meadow land in Southfield. In addition he and the right to graze beasts on the home common as well as the more distant Gobson Common.

For all this Cooper paid a Lord’s rent of 2s [2 shillings about 5p] and a ‘heriot’ also of 2s. These two payments are of feudal origin. The ‘unfree’ service that previous generations of copyholders had given to the lord in exchange for the land had long since been replaced by the annual rent of 2s. One feature of copyhold tenures was that the terms had to be by the custom of the manor and one of these was that the rent could not vary and might well have been set at this level centuries before. The heriot was a remnant of what was known as a feudal incident and unusually in this case was for a monetary payment. Commonly the heriot was for the new tenants ‘best beast’ [cow].

Copyhold tenures were of immense value to the tenant for they were, in the case of copyhold for lives, de facto, perpetual leases, and in the case of copyhold of inheritance effectively freehold. It might be thought that the lord of the manor had all the power and prior to the Black Death [approximately] the lord could in fact do pretty much what he wanted. In the centuries afterward however the balance of power moved “For” as Blackstone noted “the custom of the manor has in both cases so far superseded the will of the lord, that, provided the services be performed or stipulated for by fealty, he cannot, in the first instance, refuse to admit the heir of his tenant upon his death; nor, in the second, can he remove his present tenant so long as he lives.”

Life Leases

Copyhold tenures were not popular with landowners but it was not always in the tenants favour. When a tenant died the landowner got the heriot and the lord could also charge them for adding a new life to the tenancy. Unlike the rent, which could not be varied, the fee for adding a new life was based on some multiple of the market value of the land involved. This could be up to twenty times the value but the problem for the lord was that such payments might only arise once in the landowner’s lifetime. Many were not prepared to wait as they were rarely able to realise the true value of the estate or to rid themselves of tenants who either neglected the land or could not afford to maintain or improve it. If for some reason the copyhold had to be surrendered without any lives on the tenancy then many landowners let them lapse.

Stevenson in his Board of Agriculture report on Dorset [1812] noted that “copyhold tenures in this county are now become very few, owing, it is presumed, in a great measure to the frauds practised on the respective lords of manors, by the customary tenants marrying in the last stage of decrepid [sic] old age very young girls by which, according to the custom of copyhold tenures in this county, the widow is entitled to her free bench on the husband’s copy hold. The few copyholds-now existing, consist chief of a mere cottage and garden, without any other lands being attached to them.”

Unsurprisingly 18th and 19th century manorial lords tried to extinguish copyhold as often as they could. This was relatively easy for if custom was broken in any way or if the tenant failed to apply for admission of an heir the copyhold was lost for ever. Thomas Hardy deals with the latter situation in “Netty Sargent’s copyhold” a short story from his book ‘Life’s little Ironies’. In this story Netty lives with her uncle who is the last life on the copyhold of a small cottage.

“This house, built by her great-great-grandfather, with its garden and little field, was copyhold—granted upon lives in the old way, and had been so granted for generations. Her uncle’s was the last life upon the property; so that at his death, if there was no admittance of new lives, it would all fall into the hands of the lord of the manor. But ’twas easy to admit—a slight “fine,” as ’twas called, of a few pounds, was enough to entitle him to a new deed o’ grant by the custom of the manor; and the lord could not hinder it.”

The problem was that her uncle was neglectful of arranging her admission to the copyhold. I will not spoil the story but suffice it to say that Netty won through and was added to the tenancy.

Hardy has two other mentions of copyhold both from his novel ‘The Woodlanders’. The first is an interesting comment on the superior status of the copy holder. In the novel a man has just died and his daughter Marty sits with him,

“Beside her, in case she might require more light, a brass candlestick stood on a little round table, curiously formed of an old coffin-stool……The social position of the household in the past was almost as definitively shown by the presence of this article as that of an esquire or nobleman by his old helmets or shields. It had been customary for every well-to-do villager, whose tenure was by copy of court-roll , or in any way more permanent than that of the mere cotter, to keep a pair of these stools for the use of his own dead; but for the last generation or two a feeling of cui bono [to whom it is a benefit] had led to the discontinuance of the custom”

The second reference shows how copyhold tenures could be lost and replaced by a less secure tenure – the life lease. The hero of the book Giles Winterborne was to lose his house [as was Marty above].

“He marveled what people could have been thinking about in the past to invent such precarious tenures as these; still more, what could have induced his ancestors at Hintock and other village people to exchange their old copyholds for life leases”.

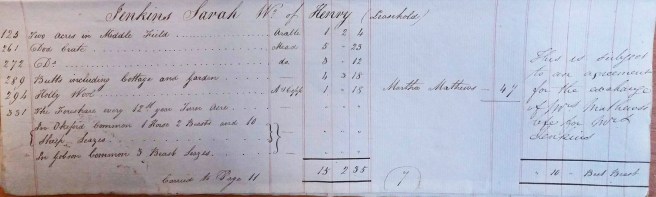

Records of life leases do not appear in the early 17th century court roll for Child Okeford and it is not until the 19th century that we have the next set of records. Here is a record of a lease for lives tenancy from the 1826 survey. Superficially it looks like a copyhold. The land held is recorded together with the lives [in this case only one], the rent, a heriot and there is a marginal note to the effect that “This is subject to an agreement for the exchange of Mrs Mathews life for Mrs Jenkins.”

Thomas Hardy describes how South’s copyhold was lost.

“They were ordinary leases for three lives which a member of the South family, some fifty years before this time had accepted of the lord of the manor in lieu of certain copyholds and other rights in consideration of having the dilapidated houses rebuilt by said lord.”

The South family had surrendered the copyhold in return for a service by the lord, rebuilding the house, which was not the lord’s responsibility under the terms of the tenure. Once the cottages had been surrendered the copyhold was terminated and could never be recreated.

No doubt the superficial similarity between the form of the tenures reassured the tenants but beyond that all was show. Unlike with a copyhold tenure, where lords had a common law obligation to admit a new person to the tenancy, there was no such obligation with life leases. In the case of Child Okeford and in Hardy’s novel, the lord had made specific, and one off provisions.

“Pinned to the parchment of the indentures was a letter ….to the effect that at any time before the last of the stated lives should drop Mr Giles Winterborne or his representative should have the privilege of adding his own and his son’s life remaining on payment of a merely nominal sum; the concession being in consequence of the elder Winterborne’s consent to demolish one of the houses and relinquish it’s site which stood at an awkward corner of the lane and impeded the way.”

Such life leases would in turn disappear in time to be replaced by simple leases for a single life for a period of years.

In 1852 an act for the Enfranchisement of Copyholds was passed which allowed copyholders to request their overlords to sell them the freehold. Various acts were passed before and after this time until in 1922 The Law of Property Act abolished all tenures other than freehold or lease hold thus ending many centuries of medieval tenures.

Tenants in fee simple

The feudal system survives into the present day. You are still technically a tenant even if you have paid off your mortgage. Should you die without leaving a will and having no living relatives with a claim on the estate your property will revert to the Crown. A government division known as Bona Vacantia compiles a list of such estates – there are currently 6269 estates on the list. [September 2023]

Your estate is a ‘fee’ as almost all such estates in England are as the form of tenure developed under the feudal system and fee, in this context means ” an estate in land or tenements held on condition of feudal homage”. And as for the ‘simple’ that implies that you have absolute ownership and that the estate is not entailed in some way such as being held in trust for your use but without you having the right to dispose of it as you will. But that is another story.

Updated 03/09/2024

Categories: In Depth