For many centuries the manor was almost completely self-sufficient. The lands of few manors provided iron ore, coal or other minerals but in most other respects the land offered the villager pretty much all of the essentials of life. To access all the bounty of the land though the villagers [or at least certain of them] had to have rights of common over it. In the next three posts we consider the land that was available to them starting with the arable lands.

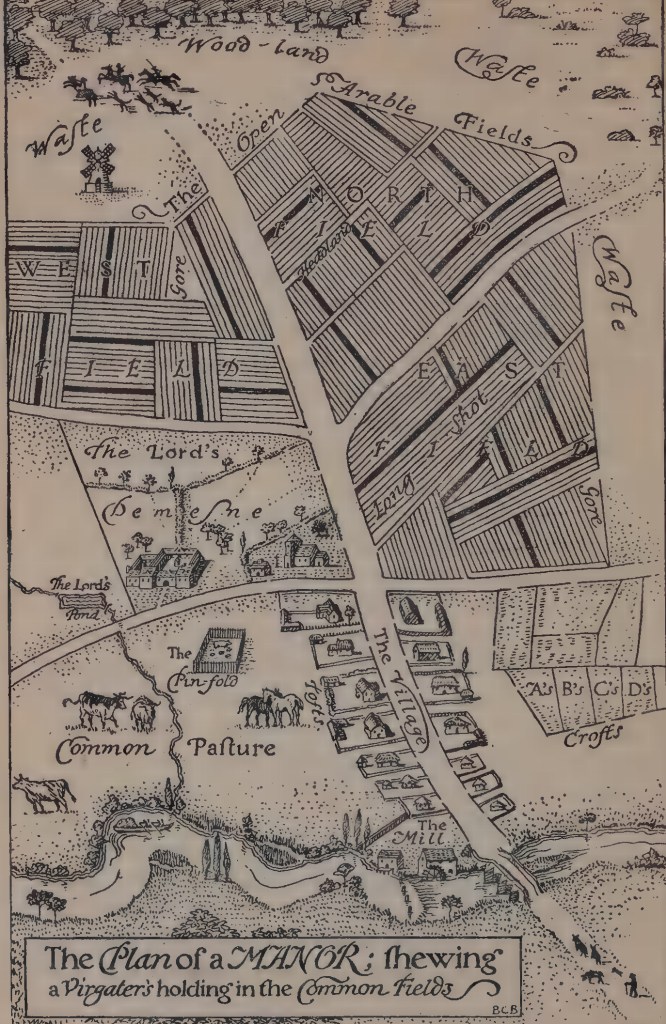

Many authors drew their idea of what a manor had looked like in ‘the old days’ and this is one of my favourites. It is taken from Nathaniel Hone’s ‘The Manor and Manorial Records, which, though it was published in 1906 aims to mimic a much earlier style; note the old fashioned ‘f’ for an S.

Hone’s picture of the manor is a charming view of life in what we may presume to be an idyllic village. The only inhabitant who does not regard it as idyllic is the local fox [a small dot in the road] who is fleeing the huntsmen.

In the centre of the manor is the manor house surrounded by the lords ‘demesne’ land. The lord generally did not farm in the open fields and we can see that his demesne consists of at least three arable fields which, as there was no need for it to be ploughed in strips, has a homogeneous appearance. This particular manor house is very grand but not every manor had its own manor house. Where the lord held many manors it was not necessary to provide such a grand building in each one. Local management of the manor was generally then held by a Steward who visited regularly or the tenant of the demesne farm usually called ‘Home Farm’. Note how close the church is to the manor house. As the lord of the manor was the original patron of the parish church it was built in part of his original holdings, not too far for him and his family to walk to on Sunday.

The title of the plan refers to ‘a virgater’s holding’. A virgate was some 20 to 30 acres in extent and so we might assume this map refers to the estate of an ‘average’ land holder and commoner in the parish. A man who many would refer to as a ‘yeoman’.

There are three large open fields producing arable crops, here labelled North, East and West field, which are subdivided into numerous long narrow strips. In a large parish there could be several hundred strips in each field. The strips themselves were grouped together in what were called ‘furlongs’, yet another use for this word, and orientated according to the lie of the land to aid drainage. There were too many strips to name each one, but the furlongs were frequently named and one here is called ‘Long shot’ whose meaning is obscure.

Each tenant of the manor held a variable number of strips [1] in the open fields. In this case the virgater holds twenty five strips [blacked out]. They are seen to be distributed across all fields, This was necessary and as each year one field had to be left uncultivated or ‘fallow’, to maintain soil fertility. Had all his strips been in one field his family would have starved in that year. It will be seen that he has eight strips in two of the fields and nine in the other and that none of the strips were laid next to each other.

This crop from John Martin’s pre-inclosure map of Chilfrome shows this effect in what was once real life. It was commissioned by Lord Sherborne and his lands and those of his tenants are shown as red and yellow strips with the names of the tenants written in. The white strips belong to an unnamed owner. Mr Porter can be seen to hold three strips in this area but none of them lie next to each other.

Martin has followed the usual convention for un-inclosed fields in that the strips are separated by hatched lines. Inclosed land was always delineated by solid lines. To work the fields required collaboration between the villagers, but the manor was not some kind of early form of commune or kibbutz: the land was not owned by some form of cooperative instead the commoner held each in what is known as severalty. When the ownership [2] of land is shared, it is referred to as ownership in common, but when the ownership resides in just one person, when its ownership has been ‘severed’ from any other possible owners, it is said to be held in severalty; all the strips in the open fields were held in severalty.

Very occasionally the custom was that the strips would be allocated to the tenants each year by drawing lots but in most manors the ownership of individual strips was fixed and the fact that so few tenants had strips laid next to each other suggests that originally there was some system designed to keep them apart, presumably with the intention of evening out the differing qualities of the land in the fields.

How then was the arable field used for grazing? Well for much of the year of course they couldn’t; it was not generally a good idea to let cattle amongst the crowing crops. After the corn harvest, during the crucial autumn and winter months, they came into their own. To ensure continued fertility of the fields the crops they grew had to be rotated, an invention it is said of the Romans, who adopted the policy known as ‘food, feed, [3] fallow’. The food was wheat, for the humans ; the barley or oats was feed for the animals and the fallow was to allow rejuvenation of the field by resting it. It might be mentioned here that though oxen were pretty hardy beasts and were often fed loppings and toppings, the growing tips of tree branches and gorse, it appears they are not devoid of taste; it was said that they preferred barley straw to wheat straw.

If we take one field we can see how it was used, bearing in mind that although the farmers held their land in severalty the planting of the field had to be in common. You could not have wheat in one strip and barley in the next for example. The whole field had to be planted with that years crop. Our chosen field had been planted in the previous winter with ‘winter’ wheat [4] and we enter the field in late summer just as the last sheaf of wheat is being removed from it.

In the distance the church bell is being tolled announcing that the field had been ‘broken’. It is hardly needed as all the commoners who occupy the strips are already driving their livestock onto the field. The arable fields then were much different to today’s. Hand reaping rarely cut the wheat short, so the stubble was inevitably left long. In the absence of herbicides there were also plenty of weeds and grass growing to supplement the stubble. In later centuries clover or other nitrogen fixing plants were planted along side the wheat and now, un-shielded from the light they began to grow vigorously. Ideal fodder. Then again hand reaping also left a trail of shed corn and heads of wheat which the cattle could devour. Until the late 18th century this particular crop had been the prerogative of the human animal. For countless centuries women and children had ‘gleaned’ the open fields for these but a legal decision in 1788 declared that particular custom to be illegal [see here for further discussion https://johnmartinofevershot.org/the-open-field-system-2/] and after that time the cattle were left to enjoy the shed wheat on their own.

The stubble was not the only form of grazing in the open fields though. Anarchy would have resulted had not the farmers left ‘green lanes’ to access the furlongs and these ‘headlands’ or ‘baulks’ afforded good grazing. The fields themselves were several hundred acres in size but, as in the manor above, irregular in shape and rarely smoothly contoured. The result was that there were always odd bits of the field that were not cultivated. At the corners there were triangular segments called ‘gores’ and wet areas, odd steep hillocks, deep depressions and steep banks, known by the general term ‘sikes’ which were all left uncultivated, as were the domed or embanked round and long barrows of the neolithic period.

These areas were a problem for the farmer to cultivate but not for the cows to graze. Depending on their size sikes, headlands and gores were often let out privately in the summer for grazing but as the animals could not be allowed to roam free over the arable fields they were quite literally tied up in what was called tether grazing.

Before the 16th century, for a few happy months after the harvest, the cattle wandered around the open fields, their natural functions helping to manure the soil; their ultimate fate however had been already decided. In a good year the hay harvest, straw and such pasture as there was, would carry the draught animals through the winter; all other animals were slaughtered and salted down.[5]

To return to our ex-wheat field. As winter drew near the draught animals were taken off and the ex-wheat field was now prepared for its transformation into the spring corn [6] field. Traditionally ploughing for this began on Plough Monday, the first Monday after 12th night after which it was sown with barley, oats or beans. When that crop had been harvested in late summer the spring field now became the fallow field for the next year. Before the 16th century, when various ‘leys’ were introduced it was left to rest on it’s own, natural herbage quickly invading it. It would be grazed initially by cattle for a month or two, and then by sheep, until the following October when the fallow field would be ploughed and sown with winter wheat.

The possession of arable land was the usual prerequisite for a tenant to be a commoner and right to graze on the arable fields after the harvest was generally restricted to the severalty owners of the strips and was called a ‘common of shack’. Very occasionally other commoners were allowed to graze on the arable and some lands were ‘lammas’ lands. We will explore these later. A summary of the various types of land and their ownership is shown below.

[1] STRIPS: These are also known as ‘selions’ or simply ‘lands’.

[2] OWNERSHIP: Technically only the crown could own land. Everybody else ‘held’ an estate in land but for simplicity we will say they owned their various plots.

[3] FOOD FEED & FALLOW: The general name for the cereal crops was ‘corn’.

[4] WINTER WHEAT: Wheat requires a long growing time and so is planted in the autumn and although it does not grow much over the winter it is ready for a quick get away, as it were, when the warmer spring weather comes.

[5] SALTED DOWN: Of course the next generation of draught animals had to be supported as well. Oxen could not be trained to plough until their third year. Their life span varied but their fate was the same as all farm animals when they had to retire – they were eaten. Hardly the retirement we dream of for ourselves.

John Martin gives a recipe for ‘salting’ the meat to keep it good for a few months at least. It is shown here as you never know when it might come in handy!

[6] SPRING CORN: This could be barley, oats or beans.

Categories: In Depth