The title page of the first volume of the first edition of Hutchins.

The most famous historian of Dorset was John Hutchins and his most famous work was the ‘History and Antiquities of the County of Dorset’. For anyone interested in the people and places of Dorset it essential reading.

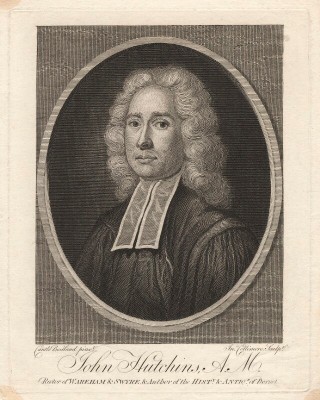

John Hutchins by J. Collimore, after Charles (Cantelowe, Cantlo) Bestland line engraving, published 1813 NPG D8641 National Portrait Gallery

Hutchins was born in 1698 at Bradford Peverell just a few miles north of Dorchester. His father was curate there and his whole upbringing was steeped in religion. He attended Hart Hall, Oxford and was subsequently ordained at the age of 24 returning to Dorset as curate to the vicar and master of Milton Abbas grammar school. Comparatively late in life, when he was forty, he was made rector of the parish of Swyre and then at the age of forty five to Holy Trinity, Wareham. Had he survived into the next century he would have become that most reviled cleric -a pluralist claiming the livings from two parishes. It is not known how effective he was as a rector as the Dictionary of National Biography notes: “Political excitement among his parishioners at Wareham involved him in difficulties, and his weak voice and growing deafness diminished his influence in the pulpit.”

When his interest in the history of Dorset was first stimulated is not known but in 1737 whilst working at Milton Abbas “Jacob Banks Esq of Abbey-Milton (whose memory I must ever revere…)” commissioned him to do some work on the life of one John Tregonwell which in turn led him to start collecting historic manuscripts and one thing led to another. In 1739 he sent out a circular letter to various notables in the county containing just six questions and so began to put together his great work. For the next twenty three years he built a massive collection of papers which in July 1762 was almost destroyed when the town of Wareham, including his rectory, were burnt down. Fortunately his wife risked her life to rescue the papers and his work continued for another eleven years before he died, having suffered a stroke, in 1773. At the time of his death the work was unpublished but the majority of the work having been completed, the first edition was published in 1774, in two volumes.

His son in law, John Bellasis, oversaw the publication of the second edition, which was to be published in four volumes, but it had a very rocky start. The first volume of the second edition was published in 1796, the second volume in 1803 and then disaster struck when a fire at the publishers destroyed all the unsold copies of volume 1 and 2. Worse still it destroyed all the copies of volume 3 bar one. Then John Bellasis died in 1808. The mantle was taken on by others however and the third volume of the second edition appeared around 1813 and the final fourth volume, appeared in 1815. Such was the fascination with the subject that a third edition followed under the editorship of William Shipp and James Hodson. It was eventually published in four volumes 1861,1864,1868 and 1873.

The first edition can be found at archive.org to download. The second edition does not appear to have been published on line and I am embarrassed to say that although I have a copy of the third edition that I found somewhere on the internet – I have forgotten where I got it from and searching has failed to find it.

Both the first and third editions cover the general history and topology of the county and also offers what he calls a Dissertation on Domesday Book. Given the 88 year difference between the two editions it is not surprising that the editions differ somewhat. The later editions contain a number of illustrative plates of various large houses in the county together with genealogical tables of the ‘great’ families of Dorset. There is, in addition, a little more original research in the third edition and of course the ownership of various manors had been updated.

The interest of the book lies in the entries for individual parishes. Anciently there were a number of ways in which the administration of counties was arranged ; the two commonest were the grouping together of parishes in units known as ‘Hundreds’ whilst other places were ‘Liberties’ and Hutchins lists the villages and parishes according to these.

A typical entry begins by giving the name of the parish, together with it’s ancient alternatives. For example Sydling St Nicholas had at one time been known as Broad Sydling or Broad Sidlinch. The situation of the parish in the county is normally given, together with a general description of the land, and the size of the parish. Next there follows a discussion of the Domesday entry for the parish if any. A surprising number of places are not mentioned in Domesday. Next there follows what can only be described as a genealogy of the ownership of the parish from as far back as he can find records. Since this can often be back to Anglo-Saxon times the entry can be both extensive and abstruse. Worse still in some entries there are extensive tracts in Latin.

As we come to more modern times [the 17th century] we see the emergence of numerous dynasties in the county and the third edition contains extensive pedigrees of those in the parishes in which he lived. Naturally given that he was a clergyman he spends a lot of time discussing the parochial church, the various monuments in it and all it’s previous incumbents.

If this sounds rather dry and somewhat tedious – well it can be. But, and this is where Hutchins is a joy to read, it is almost as if he himself may have realised this. In Hutchins can be found the waxing and waning fortunes of places and people now long forgotten.

“Ashe, anciently a manor and hamlet, long since extinguished and depopulated…about a mile N. from Stour-Pain”

“this manor and lands here in Shilling Ockford… were held by Capel, value £17. Arthur one of his descendants was created by Lord Capel in 1641..He served his unfortunate sovereign with great courage and unblemished fidelity, and being taken prisoner on the surrender of Colchester was beheaded 9 March 1648.”

Some of his descriptions of the parishes are almost poetic, worthy of Thomas Hardy himself, and he appears to delight, whenever he comes upon them, in relating stories of the people and places that he wrote about. There is the lord of the manor at Owermoigne hung by a silken noose for murdering two guests and burying them in his cellar ; or the owner of Sydling who having run up debts of £20k [£2m in today’s money] was imprisoned for life at Ilchester Gaol. But being the owner of a manor had some perks and he made good by training as a Doctor and was even allowed out to treat patients in the area surrounding the gaol which served more as a hotel for him than a gaol.

At the end of the day, whatever Hutchins’ faults, if anyone is interested in the history of Dorset they simply have to have a copy on their desktop. Few of us today could afford an original copy of either edition but fortunately it can be downloaded here.

Categories: In Depth